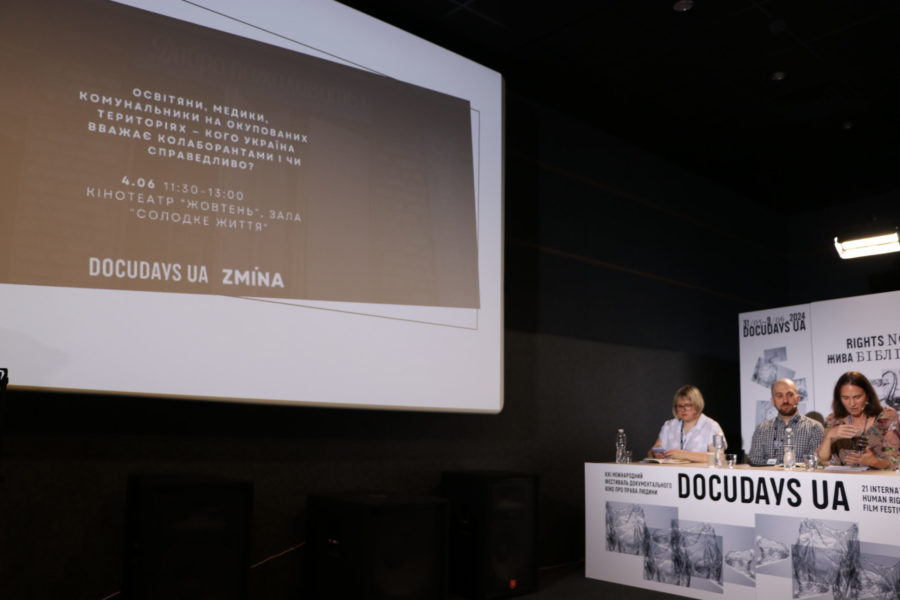

Participants of Docudays UA 2024 discussed the responsibility for the work of educators, doctors and utility workers in the occupation

On June 4, Human Rights Centre ZMINA held a discussion on whether there should be punishment and what kind of punishment should be for educators, doctors and utility workers who remained working in the occupied territories. The event took place within the framework of the Rights Now Docudays UA 2024 human rights program.

According to the advocacy manager of Human Rights Centre ZMINA, Alena Lunova, the state currently has a clear vision of who should be held liable for working in the occupation – people who work for the occupying administrations and help the Russian regime to gain a foothold in the occupied territories. At the same time, Ukraine does not have a specific answer for those workers who, according to the Geneva Conventions, can maintain the standard of living in the occupied territories that was before the occupation.

Noel Calhoun, the Deputy Head of the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission, says that under international humanitarian law, the occupying power has a responsibility to the civilian population and must provide all basic needs, such as food, water, education, healthcare, transport, etc. At the same time, the occupying power has the right to force people to work, for example, in schools, hospitals and other positions necessary for life support, and the occupying country is prohibited from recruiting its citizens from its territory.

“The big problem is that the Russian Federation does not see itself as an occupying power and as a state with obligations to IHL. It sees itself as a sovereign power after holding an illegal “referendum” and so-called “elections” and is putting pressure on people to obtain Russian passports”, Calhoun said.

In fact, Russia obliges all state employees, including teachers and healthcare workers, to obtain Russian passports, sign Russian employment contracts and work under Russian laws in Russian institutions. This can even be done through detention, torture or threats.

As noted by Noel Calhoun, if, according to international law, it is acceptable for the occupying power to force people to work in the healthcare and education sectors, it is logical that national legislation should also consider it acceptable for such citizens to continue working in these positions.

“People should not be prosecuted for collaboration just for doing their job. However, the imposition of its own systems by the occupying power and forcing people to swear allegiance is a violation of international law. In other words, it is okay to force teachers to teach. But to force them to teach according to the Russian curriculum, in the Russian language, to sign an employment contract, and so on, is a violation. Who should be held responsible for this: the occupying state, which unlawfully forced people to take an allegiance, or civilians who swore allegiance to the Russian Federation partly because of violence or threats? Or because they had no choice and needed to keep their jobs and secure their families?”, reflects the Deputy Head of the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission.

She added that legislation on collaboration should be updated. Although there are a number of legislative initiatives in the Verkhovna Rada to update the legislation to make it more closely aligned with international standards, these draft laws are not moving forward at the moment.

The educational ombudsman of Ukraine, Serhii Horbachov, believes that when judging the work of educators in the occupation, one should take into account their voluntary choice:

“Voluntariness determines whether a person is held accountable or whether they did it under coercion, under threat to life and health. Therefore, this is a really terrible problem, and this problem also lies in the fact that education is a field of worldview formation. Because if we are talking about working for the occupiers as electricians, utility workers, doctors, where it is necessary to save all people, then everything is more or less clear and falls under the criteria of IHL. But when it comes to the formation of worldview, it is much more difficult to define”.

He also adds that Ukrainian legislation does not clearly define the norm as a prohibition to engage in teaching activities in the occupation, and in fact such a judgement is left to the discretion of judges.

“But the most important problem is that the state has not yet found a balance of opinions, a point of equilibrium in legislation between human rights and national security”, Horbachov says.

The advocacy manager of Human Rights Centre ZMINA, Alena Lunova, added that it is not clear who will work in the education sector after the de-occupation of the territories, as we are talking about the need for almost a hundred thousand people. A separate question is who exactly and how the state will attract to these positions, considering the need for lustration mechanisms after the liberation of the territory.

Alena Lunova

Alena LunovaOleksii Arunian, a journalist of the publication “Hraty”, used the example of the de-occupied Lyman in Donetsk region to describe how people had to survive and earn money in the occupation:

“After the occupation of Lyman, it was quite difficult for people to live there, because the city was destroyed and there was no work. The only large enterprise that was there was the railway, and it was also destroyed. And the only chance to earn money is to work for the enterprises that the occupiers created on this territory. In particular, these are the occupation administration and electricity, gas or water utilities. What happened after the de-occupation? The people who headed the occupation administration immediately fled, not waiting for the Ukrainian army to enter the city and be detained by the SBU. But then many people were prosecuted for collaboration anyway. Who were these people? Mostly those who held some ordinary positions in the occupation administration, such as watchmen, secretaries, technicians, or people who had senior positions in public utilities”.

For example, Arunian continues, one of the cases that demonstrates this situation was about a local electrician, Dmytro Harasymenko, who headed the electricity service during the occupation. His task was to set up electricity supply networks in the city, for which he was detained and arrested after the de-occupation.

“He was accused of doing business with the occupying state, and he pleaded guilty. But he said that he took the position because he could not evacuate to the free territories because his parents were sick and they needed money. Secondly, the city needed electricity, which was requested by the citizens themselves. He said: I was thinking about my family and the community”, the journalist says.

Then the court of first instance nonetheless sentenced the man to three years in prison, but the appeal took into account his position and the fact that he had not harmed the state, was not pro-Russian and did not go to work for the occupiers because of his pro-Russian views, and the court released Harasymenko on probation.

Oleksii Arunian

Oleksii ArunianAt the end of the discussion, Oleksii Arunian pointed out that the state should find a balance between its own interests in the context of national security and the interests of Ukrainians in the occupation:

“Now there is a certain imbalance, I think, towards the interests of the state. But the legislation should also take into account the situations that people face during the occupation. And this is important not only for these individuals, but also from a strategic perspective, and for the state as well. Because if people in the occupied territory perceive Ukraine as a threat and do not understand why they will be punished, this will, in particular, affect Ukraine’s military success”.

You can watch videos from the event here (part one) and here (part two).

All photos in this article were taken by Iryna Ivanchenko / ZMINA.

Cover photo: Docudays

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.