Russia using enforced disappearances as method of waging war – human rights defenders

Since February 24, Russia has unleashed massive abduction of Ukrainians in the newly occupied territories, using torture and in some cases executions. The Russian Federation started to practice enforced disappearances as a method of intimidation and suppression of resistance back in March 2014 during the occupation of Crimea, resorting to it even more often in the so-called “LPR/DPR”. However, with the new wave of aggression, enforced disappearances have become a mass phenomenon.

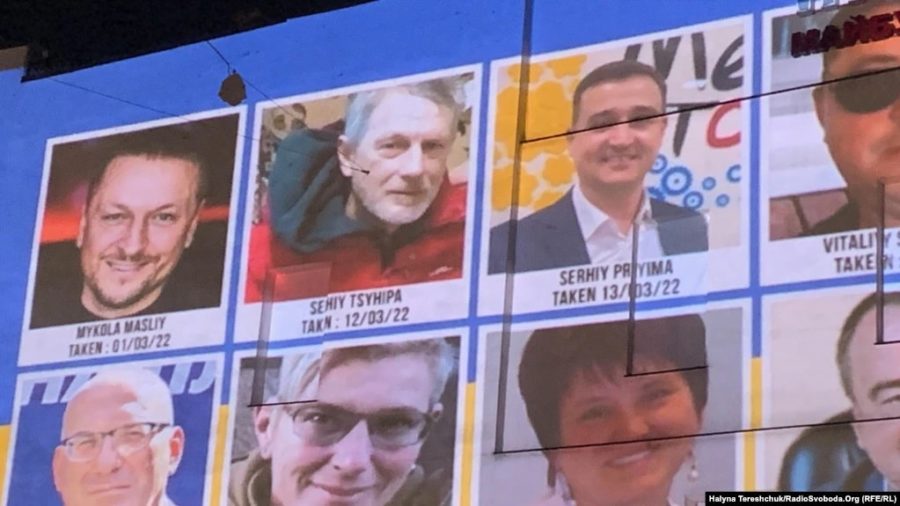

Faces of Ukrainians abducted by Russia are shown during a rally in Lviv. Photo: Radio Liberty

Faces of Ukrainians abducted by Russia are shown during a rally in Lviv. Photo: Radio LibertyTetiana Pechonchyk, Head of Human Rights Centre ZMINA, made a corresponding statement at an online conference on the occasion of the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances on August 30.

Since February 24, ZMINA has documented at least 311 cases of the enforced disappearance of Ukrainians in the newly occupied territories. The victims are active members of local communities, including representatives of local self-governments, journalists, volunteers, educators, religious and cultural figures, activists who did not agree with the occupation, or members of their families. Of those, 181 people have been released, but 118 are currently missing or held in Russian captivity.

“The Russian service members abduct Ukrainian civilians daily, regardless of their status. Our organization has managed to document only a small part of these criminal practices pursued by the occupiers. At the same time, we can say with confidence that activists and volunteers, local self-government officials, educators and other people who actively express their position are at particular risk of enforced disappearance. To date, we have recorded at least 127 cases of abductions of activists and volunteers, 98 – of local self-government officials, and 28 – of educators,” ZMINA researcher Nadiya Dobrianska said.

Twelve people were tortured or killed in captivity or died after release not surviving the torture, Dobrianska continues. In particular, Olha Sukhenko, head of Motyzhyn village, her husband Ihor, her son Oleksandr, volunteers Serhiy Kubrushko, Andriy Shostak, Serhiy Piskotin, and a Czech volunteer named Tomáš were killed after being abducted in Kyiv region.

The Sukhenko family killed by Russians in Kyiv region

The Sukhenko family killed by Russians in Kyiv region“Out of the data documented by ZMINA, the largest number of missing Ukrainians has been recorded in the occupied south of Ukraine: 119 people have been abducted in Kherson region, and 90 more – in Zaporizhzhia region. There are currently known 27 cases of enforced disappearances in the occupied areas of Kharkiv region. At the same time, there is little information from the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions due to active hostilities and poor communication. Therefore, our calculations cover 45 enforced disappearances in Donetsk region and two cases in Luhansk region, although it is clear that these figures may be much higher as we lack the information from occupied Mariupol,” the human rights activist adds.

Human rights activists point out that Russia also often kidnaps relatives of Ukrainian service members, veterans, representatives of law enforcement agencies, local entrepreneurs, and other people.

In 2014–2021, CrimeaSOS documented the enforced disappearances systematically. In particular, 44 cases of enforced disappearances were recorded in Crimea, 15 of them related to people whose fate and whereabouts are still unknown.

“Fifteen victims who have not yet been found are activists Tymur Shaymardanov, Seyran Zinedinov, Isliam Dzhepparov, Dzhevdet Isliamov, Eskender Apseliamov, Mukhtar Arislanov, Ruslan Haniyev, Arlen Terekhov, Ervin Ibrahimov, Eskender Ibrayimov, Valeriy Vashchuk, Ivan Bondarets, Vasyl Chernysh, Fedir Kostenko, and Arsen Aliyev. These victims of enforced disappearances are pro-Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar activists or their relatives. In this way, the Russian authorities suppressed the voice of activists on the peninsula in the beginning, and Russia is acting in the same way in the newly occupied territories now,” says Oleksiy Tilnenko, Head of the Board of CrimeaSOS.

Tilnenko adds that their organization has a separate hotline for cases of prisoners and enforced disappearances since March 2022, calls are received both from relatives of prisoners of war and civilians abducted by representatives of the Russian armed forces.

“Currently, our hotline alone has received more than 1,000 appeals. We cooperate with specialized government agencies to make sure that every case is recorded so that appropriate efforts are made to release our fellow citizens,” says the human rights defender.

Tetiana Katrychenko, the coordinator of the Media Initiative for Human Rights, notes that Russia is holding Ukrainians in occupied Crimea, in detention facilities in Bryansk, Belgorod, Kursk, Rostov, and Ryazan regions of Russia. Civilians are often held next to military personnel and even in the same cells. Also, many Ukrainians are held in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine.

“Speaking of detention facilities in Donetsk region, there can be previously created so-called pre-trial detention centers of Donetsk, colonies No. 32 97 in Makiivka, No. 127 in Snizhne, No. 52 in Yenakieve, etc. And there are also new detention facilities, as already well-known colony No. 120 in Olenivka, Volnovakha district, or a police station in Starobesheve,” Katrychenko says.

The expert underscores that Ukrainians are kidnapped for several reasons: indiscriminate detentions, when the Russian Federation tried to replenish its “exchange fund” as much as possible in northern Ukraine in February-March; attempts to encourage cooperation; active position of citizens and communication with representatives of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, as well as checks for loyalty to the occupation authorities and “filtration”.

Occupiers searching a civilian. Photo credit: Stringer/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Occupiers searching a civilian. Photo credit: Stringer/Anadolu Agency via Getty ImagesDmytro Lubinets, the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, calls on relatives of missing persons to contact first and foremost the National Police to file a missing person report. Next, relatives should contact the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights and the Commissioner for People Gone Missing, as well as the National Information Bureau at 1648.

“Since the full-scale invasion started, the practice of enforced disappearances has become one of the common methods of intimidating citizens in the newly occupied territories. Such disappearances have become a hallmark of Russian policy in Chechnya as from 3,000 to 5,000 people have fallen victim to it since 1999. It is what the Russian Federation practiced for eight years in the territory of occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions, as well as on the Crimean peninsula,” Lubinets comments.

Oleh Kotenko, the Commissioner for People Gone Missing Under Special Circumstances, notes that their office has been operating since the end of May. The office has a call center at 0 800 339 247, open on weekdays from 9:00 to 18:00. On weekends, the center works in remote mode, and information about the persons missing can be sent at 095 896 0421 via Viber and Telegram. Kotenko also calls on relatives of missing civilians to inform the state about abduction cases.

It is important to distinguish between enforced disappearances and disappearances, explains Maria Kvitsynska, regional consultant for Europe and Central Asia at World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT):

“When we talk about enforced disappearances, it is about cases where there is evidence or strong grounds to believe that a person was abducted by Russian soldiers, special services, etc. Such disappearances are one of the most serious violations of international law in the field of human rights and international humanitarian law and can be recognized as a crime against humanity.”

Kvitsynska advises families of missing Ukrainians to contact the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances. If a person was abducted because of their human rights, journalistic activity or volunteering, it is worth filing reports to the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders. These agencies should further send a corresponding inquiry to Russia. The third rapid mechanism is the International Committee of the Red Cross.

“All three mechanisms can and should be used simultaneously. In a more long-term perspective, such cases must be submitted to the International Criminal Court and UN committees,” the OMCT representative adds.

Olena Tsyhipa, the wife of journalist and public figure Serhiy Tsyhipa, who was kidnapped in Kherson region on March 12, calls on people not to be afraid to talk about their missing loved ones, to make these stories public, and to help each other both psychologically and with practical advice.

Serhiy Tsyhipa, who was kidnapped by occupiers, is still in captivity

Serhiy Tsyhipa, who was kidnapped by occupiers, is still in captivityVideo from the press conference

Background. Enforced disappearances are one of the most serious war crimes and crimes against humanity. International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances is marked annually on August 30. This day was established by a resolution of the UN General Assembly in 2010 to draw attention to the plight of persons imprisoned in poor conditions and places unknown to their relatives and/or legal representatives.

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.