The state should determine the only body to which Ukrainians can turn if their civilian relative has been abducted and is being held by Russia – human rights defenders

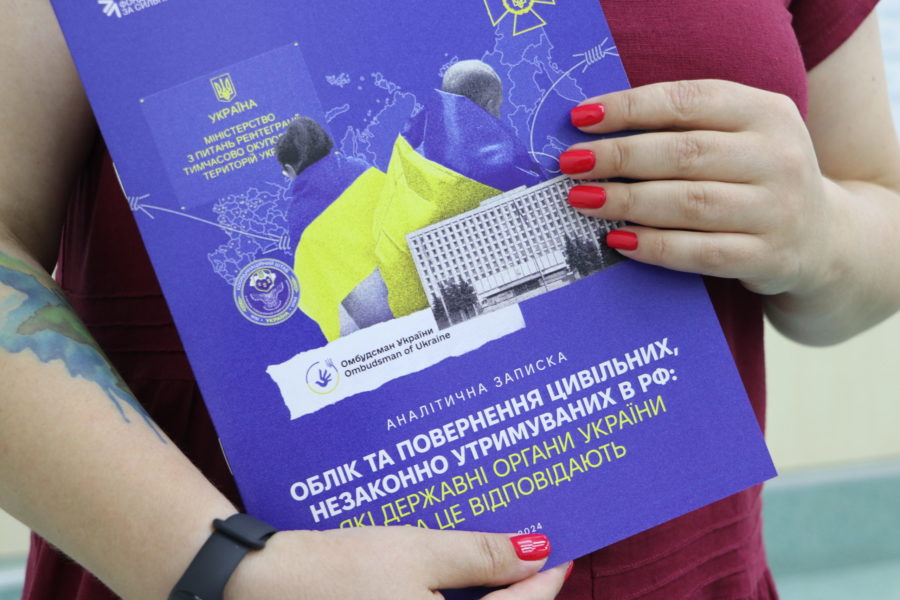

The state does not have a “single window” where the families of Ukrainian civilians illegally detained by the Russian Federation can initially apply for help. The system of bodies dealing with this issue is very wide — currently there are more than ten such bodies. In addition, these bodies’ registers of missing Ukrainian civilians are different and do not have a uniform number of detained people.

On July 25, representatives of the Media Initiative for Human Rights and the Human Rights Centre ZMINA said this during a press conference in Kyiv.

As reported by the Advocacy Director of ZMINA, Alena Lunova, Ukraine has designated state bodies that take care of the issues of persons deprived of their personal freedom due to the war against Ukraine. But despite the considerable number and branching, these structures do not form a single system in which the coordinating body is clearly defined.

Currently, the key structures that are most frequently requested for help are the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, the Ministry for the Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories, as well as the Joint Center for the Coordination of the Search and Release of Prisoners of War and Persons Illegally Deprived of Liberty as a Result of Russian Aggression against Ukraine, at the Security Service of Ukraine.

Alena Lunova

Alena LunovaAfter the disappearance of their relatives, Ukrainians are forced to turn to various structures, but, according to human rights defenders, this not only further traumatizes the relatives of Russian hostages, but also duplicates and overloads the work of state structures. Families also often do not know if there is any communication and coordination between these agencies.

“A single window will give families an understanding of where to go for help. It is important that the state finally decides which of a number of bodies will take on all this work,” the human rights activist believes.

This is also confirmed by relatives of civilians who were illegally deprived of liberty by representatives of the Russian Federation.

“A large number of organs is too complex. When you contact, for example, the Coordination Headquarters, they ask the relatives there, ‘What new information have they learned about the prisoner?’. But I want relatives to receive new information about a missing person from the state, and not the other way around. I have to constantly tell the same information about my son to different authorities,” noted Tetiana Popovych, mother of the kidnapped civilian Vladyslav Popovych in Bucha, a volunteer.

Tetiana Popovych

Tetiana PopovychAccording to Tetiana Katrychenko, Executive Director of the MIHR, due to limited powers, state bodies are not ready to take on all the work related to illegally detained civilians in the Russian Federation.

“For this analytical report, we conducted a small survey of the families of civilian hostages. One of the questions: which, in their opinion, are the state authorities responsible for the registration, search and release of civilians? In practice, people, when preparing appeals, try to get information from everywhere — from local deputies to the Office of the President of Ukraine. They even unite in public organizations, because it is easier to communicate with the state. But in the end, they cannot get answers to their questions and determine which state body can help,” comments Katrychenko.

Tetiana Katrychenko

Tetiana KatrychenkoZMINA’s Advocacy Director Alena Lunova also points to another problem — all bodies that in one way or another deal with illegally detained persons in the Russian Federation have different registers:

“Currently, there are at least five registers that are maintained by various bodies and where information about illegally detained persons are entered. But there is no coordination between these registers. There is not even a single figure from the state on how many Ukrainian civilians are detained by Russia. All this is because each register contains data that is in no way coordinated with the data from the rest of the registers. We have to finally determine who will be the main holder of data about these people.”

Tetyana Katrychenko believes that the state still does not have a unified system, because for a long time, it could not admit that the issue of illegally detained people in the Russian Federation is a big problem and that behind these people there are families who need support.

The text of the analysis is available at the link.

You can watch the video from the event here.

This event took place with the support of the Partnership for a Strong Ukraine Fund, which is financed by the governments of the United Kingdom, Estonia, Canada, the Netherlands, the United States of America, Finland, Switzerland and Sweden.

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.