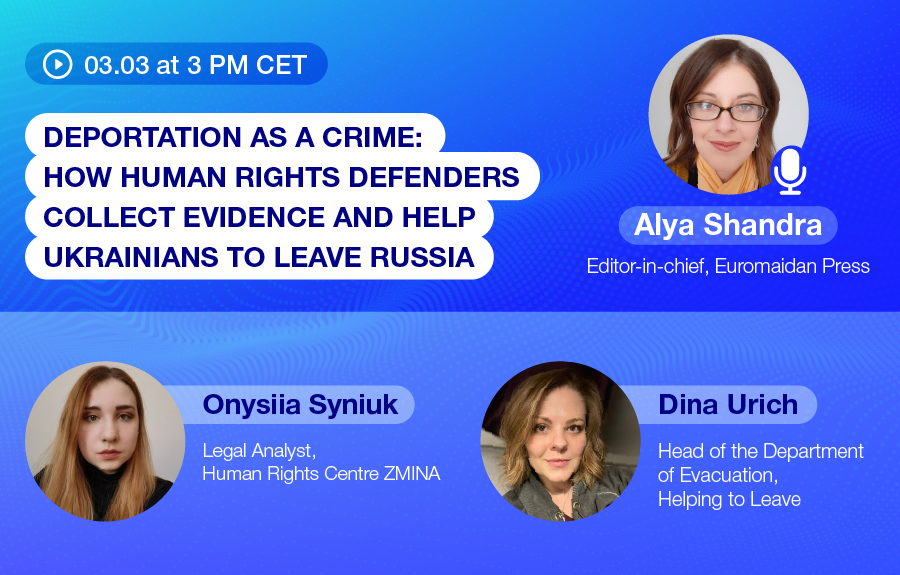

Deportation as a crime: how human rights defenders document evidence and help Ukrainians escape Russia

Russia is thought to have deported roughly 1 million Ukrainians from territories they occupied, including 16,000 children. We talk to the human rights activists who collect evidence of this war crime and help deported Ukrainians escape. In collaboration with ZMINA NGO, Euromaidan Press is holding twitter spaces with prominent Ukrainian human rights activists working to ensure Russia will not get away with its war crimes in Ukraine.

One of the most common ones is the deportation of Ukrainians on Russian-occupied territories, for which the Criminal Court recently issued an arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Human Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova.

When Russia invaded, ZMINA [“Change’ in Ukrainian] and colleagues launched the 5AM Coalition, comprising 30 prominent human rights organizations and individual experts who document war crimes committed by the aggressors in Russia’s war. In the discussion “Deportation as a crime: how Ukrainian human rights defenders document evidence and help Ukrainians to leave Russia” we dive into Russia’s most widespread war crime with Onysiia Syniuk, legal analyst at human rights center Zmina, and Dina Urich, head of the department of evacuation at Helping to Leave.

Onysia, could you please tell us more about Zmina, your work with the 5AM coalition, and how it feels to document Russian war crimes for over a year?

Onysia: Zmina has been working in the field of human rights in Ukraine for quite some time. With the full-scale invasion, we had to scale up our work to document war crimes, focusing on specific areas like deportations, torture, and other crimes. The 5AM coalition is a group of Ukrainian NGOs with different objectives, allowing us to cover more ground in addressing the numerous war crimes taking place.

We’re involved in documenting these war crimes, informing the public in Ukraine and abroad about the atrocities committed by Russia, and working on legal aid. We also work on devising accountability, rehabilitation, and compensation mechanisms for the victims of these war crimes.

As for evidence collection, we work based on the Berkeley Protocol, which involves two types of evidence gathering: open sources and field missions. We search all possible news outlets, chats, and online sources, and conduct field missions to places like Kharkiv Oblast and the Baltic states, where we interview deported Ukrainian citizens who managed to escape to EU countries.

Dina, could you tell us about your work at Helping to Leave, how it operates, whom you help, and the challenges of escaping from the occupied territories of Ukraine?

Dina: I head the Department of Evacuation from Temporarily Occupied Territories at Helping to Leave. We have a co-department that helps deported people escape from Russia and also assists people on Ukraine-controlled territories in moving towards the European Union. Our organization provides comprehensive help, including medical evacuations, evacuations for people with oncology, and humanitarian aid.

We work through a Telegram bot, where people communicate their desire to leave occupied territories or Russia. We receive direct requests from them or their relatives, who may pass on information if there are communication issues in the occupied territories.

During conversations with those willing to evacuate, we often find evidence of war crimes, tortures, kidnappings, people being held, and child deportations. This is quite astonishing, as it’s not something we directly ask about, but it spontaneously emerges from their stories. These incidents are so common that they occur in nearly every second case. We partner with rights protection organizations to pass on that evidence, including the 5AM coalition.

Onysia, can you estimate the number of Ukrainians deported to Russia and Belarus? How can it be traced?

Onysia: Estimating the exact number is difficult because Ukraine lacks access to occupied territories and diplomatic missions in Russia. The Ukrainian government relies on open sources, reports from relatives, and witnesses submitted to law enforcement or the National Information Bureau. Our numbers are largely from Russia and may not differentiate between voluntary and forced deportations. We can estimate that at least one million people have been deported, but that’s a rough number. The overall number of Ukrainians in Russia is two million, including those who went willingly. For children, the partially confirmed number is over 16,000, based on data from the National Information Bureau.

The deportation process varies depending on factors like regional control, proximity to the border, and when people were deported. In regions like Kharkiv, which has a direct border with Russia, people were immediately transported by bus to Russia. In other regions bordering occupied territories, individuals were first brought to these territories, underwent filtration, and then sent to Russia.

Civilians evacuating from occupied regions of Ukraine. Photo: Ombudsman of Ukraine

Civilians evacuating from occupied regions of Ukraine. Photo: Ombudsman of UkraineThe methods of forcing people onto buses or into Russia can differ. Some were forcibly put on buses and taken to Russia, while others faced coercion in subtler forms. Deportation isn’t just about physically moving people; it can also involve creating conditions that force people to leave. For example, in Mariupol, residents faced a lack of basic necessities like gas, electricity, and food, as well as no access to Ukrainian territory. When they asked to be brought to Ukraine, they were either tricked into getting on buses and then taken to Russia or told they could go by themselves but with no guarantee of safety, as they might be shot on their way. This also constitutes forceful deportation.

What can we say about the legal assessment of this process? Can this be considered a war crime and on what grounds?

Onysia: Deportation and forcible transfer can indeed be considered war crimes, and even crimes against humanity, if it can be proven that they are part of a large-scale and systematic attack on civilians. The transfer of children from one national group to another could amount to genocide.

Are specific categories of Ukrainians being targeted for deportation? Do they have something in common?

Onysia: Yes, certain categories are targeted, particularly children, as they are taken from newly occupied territories, orphanages, and boarding schools. Some are even sent to “summer camps” where they are not returned to their families. Other targeted groups include people with disabilities, those in retirement homes with limited capacity to refuse, and even prisoners transferred from jails in Kherson Oblast to Russian regions.

Why is Russia doing this? And what’s the point of targeting children?

Onysia: There are multiple reasons for these deportations. One reason is to clear the territory of people who could potentially support Ukraine during a counter-offensive or after the territory is liberated. Creating an atmosphere of threat and fear in occupied territories ensures that activists, volunteers, and prominent community members may try to leave, and, thus, won’t support the Ukrainian army or contribute to the war effort in any way.

As for targeting children, it may stem from Russia’s belief that Ukrainians are essentially Russians who have been misled into thinking they have a separate identity. By taking children and raising them as Russians, they aim to “re-educate” them about their identity.

Deportation of Ukrainian from Russian-occupied Mariupol. Photo: TG channel of Petro Andriushchenko

Deportation of Ukrainian from Russian-occupied Mariupol. Photo: TG channel of Petro AndriushchenkoSo, we’re moving on to another very important topic: the forced adoption of Ukrainian children. Could you tell us a bit about what we know and the scale of this phenomenon?

Onysia: As I mentioned earlier, we know that over 16,000 children have been deported, but the actual number might be higher. Regarding adoption, we know that even children initially taken to other occupied territories like Crimea are soon brought to Russia. Russian Children’s Ombudsman Maria Lvova-Belova has publicly stated that they are taking these children to find better homes in Russia.

When Putin incorporated the newly occupied territories into Russia, all citizens, including children, became considered Russian. This simplifies the adoption process, allowing these children to be adopted by Russian families, who can then change their birth dates, names, and other information, making it nearly impossible to find them afterward.

Are we talking about orphans here, or are these children with parents who are deprived of their parents?

Onysia: Russians take different categories of children, including whole institutions like orphanages, which are then transferred to Russia and dispersed throughout the country. This includes children whose parents were killed during the invasion and who may have relatives in Ukraine that the Russian side is not searching for. It also includes children in specialized institutions who might not be orphans but may have relatives in Ukraine, or whose parents have been deprived of their parental rights, or who require specialized care due to medical conditions.

Dina: In our work, we’ve received over 16,000 requests from people who were forcibly deported and are now in Russia, and we’ve evacuated 18,000 people from temporarily occupied territories to Ukraine-controlled areas. Unfortunately, the situation is quite sad, and people are being deprived of their right to escape from war conflict areas. There’s no way to leave the temporarily occupied territories and go directly to the Ukraine-controlled side. Everyone who wants to escape the war zone is forced to go towards Russia, where they must go through filtration, which can include extensive investigation, body searches, fingerprinting, and detentions without proper legal accusations.

As for children, we have received requests from teenagers brought to summer camps or deported without their parents. They sometimes write to our Telegram bot directly, asking for help. It’s an astonishing situation, and we’re doing our best to assist these children.

Onysia: I’d like to thank the Helping to Leave initiative for their incredible work in assisting people who have been deported to Russia and then managed to get to EU countries. In terms of proving the systematic and large-scale approach to deportation, filtration camps and checkpoints are important evidence. This system was pre-planned, and there are different stages of filtration that people must go through.

We have harrowing stories of people being detained and tortured, even after passing through several checkpoints and filtration camps. The goal of Russia torturing these resistors is still unclear, but it is undoubtedly a part of their strategy to control and suppress Ukrainians who are critical of the occupation.

What do they aim to achieve by breaking these people? Does Russia think that torture can accomplish this? What is their goal?

Onysia: I definitely believe that Russia thinks it’s possible to break these people. They also become examples for others, so that anyone who resists will face the same fate. Russia also tries to use these people for propaganda purposes, like the man I mentioned. They only released him after forcing him to appear in a propaganda video, claiming the special operation would be successful and Russia would win. They then randomly used his footage in other propaganda videos, making false claims about him being an Azov member and so on. So, propaganda is a major purpose for this filtration.

Dina, returning to your experience with the teenagers who contacted you to help them leave Russia, could you tell us a little about that and whether it was possible for you to help them leave?

Dina: Yes, actually, we were able to help them. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank Zmina for their amazing assistance with documents when dealing with people who have document issues. These teenagers are now in Ukraine and reunited with their family members. A major issue is that many people, after their houses are destroyed, do not have any documents like a valid passport. Russia uses this as an excuse for detention or to prevent them from leaving the occupied territories, even toward Russia. They are then stuck indefinitely because they don’t have proper documents.

Regarding the previous question about why Russia is doing this in the occupied territories — it appears to be about instilling terror, fear, and propaganda. Even volunteer work in the temporarily occupied territories is impossible unless you are a so-called volunteer who is actually part of the Russian administration authorities that completely support the war. We have a network of drivers who help evacuate people discreetly, but these drivers cannot present themselves as volunteers simply helping people because they would be held in a basement and tortured. In the Kharkiv Oblast alone, when it was occupied, five people were held in a basement and tortured just for being drivers who were helping people get out, without any proper accusations or anything like that. Any connections in society that could bring people together and possibly support resistance in the future are severely prosecuted.

Ukrainians being met by workers from Russia’s emergency ministry. Photo: Kazan Administration

Ukrainians being met by workers from Russia’s emergency ministry. Photo: Kazan AdministrationPropaganda plays a significant role in portraying Russia as saving Ukrainians. We have cases where people wrote to us saying they wanted to escape, but they were forced to participate in a propaganda video before being allowed to leave. These are the goals Russia is pursuing. As Alisa said, this is not just about extreme cases; this is a systematic deprivation of almost all human rights on the occupied territories, including the right to leave, speak your language, be united with your family, and have free communication.

That’s why we are helping people leave with our partners, including Zmina. We started a civil campaign called Territories are People to emphasize that when we talk about the occupied Ukrainian territories, it’s not just about land but thousands of people suffering under terrible conditions, similar to modern slavery. The fact that we talk about them and connect with them means a lot to them. We receive many messages thanking us for speaking with them, as Russian propaganda has led them to believe they are alone and that Ukraine has forgotten them. The fact that someone outside is talking to them, trying to help, supporting them, and understanding what they’re going through is very important.

Dina, do you think Russia’s attempts to break the will of Ukrainians with camps and deportations are successful?

Dina: We don’t think so, because we receive many requests from people trying to escape, and people cooperate a lot on the spot. There are inspiring examples of strangers helping each other’s children at the risk of their own lives. Many deported to Russia are initially afraid, but after some time, they gather the strength to continue their journey to the European Union or return to Ukraine. The psychological state of evacuees improves over time, and they are still willing to leave Russia when they can.

Could you help us imagine the journey of a Ukrainian trapped in Russian-occupied territories? Tell us what this person goes through, perhaps with an example of someone you’ve helped.

Dina: Typically, they try to find an opportunity to leave but struggle due to a lack of transportation to the front line. This is where our volunteer network comes in, with drivers picking them up even from remote villages. The journey can take days, and they may need to wait for a permit to exit temporarily occupied territories towards Ukraine-controlled ones. This permit requires extensive personal information, and the process can take days. They then find drivers to take them through the front line, sometimes under shelling. If they’re heading towards Russia, they face filtration at the border and may end up in filtration camps for days or weeks. Once in Russia, they go to refugee camps before planning their journey to the European Union or returning to Ukraine. We help by providing informational support and, when needed, financial assistance for their journey.

You also have a network of volunteers that helps even at the risk of their own safety. Is that right?

Dina: Yes, we have our own volunteers and drivers in the temporarily occupied territories, and we cooperate with local volunteers in Russia. Our volunteers that help people escape from Russia are online coordinators in the Telegram bot, as none of our volunteers are on the territory of Russia or Belarus. We work with locals to buy tickets and provide the best possible routes and checkpoints based on real-time information from those trying to escape.

Thank you so much for the work that you do. Let’s return to Onysia and hear about the legal side of this deportation of roughly one million Ukrainians to Russia. Onysia, can you tell us which organizations are involved and if they can be held responsible?

Onysia: Russians are depriving people of their right to stay in their own homes and communities, which is extremely traumatic. The Russian state and those acting in its name are responsible for these actions. This includes occupation administration officials, lawmakers creating regulations for deportations, and people like Maria Lvova-Belova, who advocates for bringing children from Ukraine. Specific individuals responsible will be revealed in investigations on a case-by-case basis. Ukraine has already opened several cases regarding deportations.

President Zelensky announced sanctions against those involved in the deportation of Ukrainian children. Is this an effective way to stop the process and punish those involved?

Onysia: Sanctions aren’t a punishment, but they can help prevent the process from continuing and make it harder for those involved. Real accountability will come later, as these individuals are currently in Russia and inaccessible for justice. The international community should put pressure on Russia in any way possible, including political pressure, economic pressure, and diplomatic means. Also, putting pressure on international organizations that might have the mandate to reach Ukrainians in Russia who can’t leave.

What about returning the deported people? What is being done and what should be done for Ukraine to track them down and ensure their return?

Onysia: Ukraine has limited resources to reach people in Russia, so the government is focusing on helping them once they’ve left Russia or are crossing the border. They’ve introduced a temporary ID procedure for those without passports, allowing them to receive identification documents in Ukrainian embassies in other countries. Ukraine is also negotiating with other countries to put pressure on Russia, and the Ukrainian ombudsman has reached out to the Russian ombudsman, though there is not much goodwill from that side.

Do we have any questions from the audience?

Peter: How do the Russians care for these children and young people who end up in Russia? Is there any information on how they are vetted?

Onysia: There is limited information, but these children go through the general Russian adoption process with the same safeguards as Russian children, which is not much. Older children with a Ukrainian identity face re-education, while younger children without a formed identity are easier to re-educate. The common theme is re-education and giving more “education” to adoptive parents to raise the children in a state-beneficial way.

A temporary facility for Ukrainians in Taganrog. Photo: Taganrog Administration

A temporary facility for Ukrainians in Taganrog. Photo: Taganrog AdministrationPeter: We know Russia moves their people into occupied territories, which is a war crime. Do they take the identity of Ukrainians living there?

Onysia: We do not have documented cases of that happening. With the larger scale of military actions, Russians are less eager to move into those territories. At the moment, the Russian military takes over houses and apartments left behind by deported people, not identities, but civilian infrastructure and civilian houses.

Dina: May I add just on the topic? First of all, I also agree with Onysia about taking over property. For instance, in Kherson Oblast on the left shore of the Dnipro that is still occupied, people are writing to us that they have nowhere to live because the military is staying in their house. They were basically kicked out and can’t do anything. This is a common occurrence – people being kicked out of their houses for the Russian military to stay there. We don’t know of cases where Russian citizens are going into the newly occupied territories due to the scale of war and military actions there. However, in terms of identity, one of the key things is that they are denying the identity of Ukrainians. The propaganda claims that there’s no such thing as being a Ukrainian, that Russians and Ukrainians are the same people. From this point of view, I don’t know of any cases of Russians moving to Ukrainian territories and then stealing their identity. That’s what I wanted to share.

Recently, Poland and the European Commission announced they want to launch an initiative to track down Ukrainian children who were deported to Russia. It would work just like a coalition of organizations that are dealing with these issues. Do you think this will be an effective hotline, an effective initiative? Is it possible to locate these children and what steps should be taken in order to return them to Ukraine?

Dina: This is a new initiative, so nothing has been shared about the procedure and the methods they will use. It’s very hard to say how it will work and if it will work. The initiative is definitely very welcome because we need all the help we can get with reaching into Russia. The Ukrainian government tried to designate Switzerland as the representative of Ukrainians in Russia, but Russia refused. We need any way possible for reaching our citizens and especially children in Russia. However, we don’t know the proposed method, so I can’t speak about its effectiveness. The fact that it’s going to be a joint effort gives me more hope in terms of it working out.

Source: Euromaidan Press

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.