Deportation in the 21st century: what you need to know about Russia’s crime in Ukraine

The word “deportation” evokes images of freight cars filled with people, accusations of entire nations as “criminals,” hunger, diseases, and massive human losses during transportation. The memory of the Stalinist regime’s deportations of Crimean Tatars, Chechens, Ingushs, Kalmyks, and other peoples in 1944, as well as the forced eviction of millions of peasants from Ukraine, Belarus, and the Kuban to Russia’s Siberia and the Far North in the 1930s, often comes to mind.

Deportation of Ukrainian from Russian-occupied Mariupol. Photo: Petro Andriushchenko, advisor to the mayor

Deportation of Ukrainian from Russian-occupied Mariupol. Photo: Petro Andriushchenko, advisor to the mayorNearly a century after the Soviet-era expulsions, Russia is again orchestrating massive deportations during its invasion of Ukraine. However, modern-day deportation looks vastly different than it did in the past. Today, it’s often disguised as “evacuation” with claims of care for Ukrainians and may involve relocating orphanages and penal facilities, transferring children to camps, and other similar actions.

However, they serve the same imperial purpose. By evicting populations on occupied territories and replacing them with Russians, Russia aims to cement its control through uprooting the ethnic composition and social structure of the invaded lands.

This article explains why the forced displacement of the Ukrainian population carried out by the Russian authorities is a crime and what are its main features and scale.

Deportation under the guise of evacuation

The Russian side frequently refers to it as the “evacuation of the civilian population” or the rescue of people, with propaganda channels showcasing videos of Russians providing shelters to Ukrainian families fleeing the conflict.

However, there is abundant evidence that this is deportation, not a friendly evacuation. The reason behind this is the frequent use of coercion, restrictions on people’s decision-making, and obstruction of departure to prevent individuals from leaving Ukraine-controlled territories.

Such actions may be classified as crimes against humanity and/or war crimes under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

As a part of these crimes, Ukrainian citizens are systematically deported by the Russians, with a system of temporary accommodation centers established within the territory of the Russian Federation and a corresponding filtration procedure implemented (read more below).

Moreover, Russia adopted several legislative acts to implement this policy.

The beginning of deportation from Ukraine to Russia

Reports about the organized displacement of Ukrainian citizens by the Russians from territories occupied after its full-scale invasion started to emerge in March 2022.

In particular, on March 26, the Minister of Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine Iryna Vereshchuk stated that Russia had forcibly deported almost 40,000 Ukrainians. On April 16, Russian media outlets informed that the Russian military had taken about 100 people, including 10 children, from Izium (Kharkiv Oblast) to Russia’s Belgorod Oblast.

However, the “evacuation” from the territories occupied before the full-scale invasion began even before February 24. And children’s institutions were one of the categories relocated first. For example, on 18 February 2022, 159 orphans were reportedly taken from already-occupied Luhansk to the Priboy hotel in the Russian town of Azov.

This practice is not new, as the campaign to relocate custodial facilities, such as orphanages and prisons, or their residents had already begun in 2014 in the temporarily occupied territories of Crimea and Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

The scale of Russia’s deportation of Ukrainians

Ukrainians arriving by train to Russia. Photo: Kazan Administration

Ukrainians arriving by train to Russia. Photo: Kazan AdministrationThe exact number of potential victims of deportation from Ukraine to Russia is unknown, but it is estimated that anywhere between 2.8 to 5 million Ukrainians, including from 260,000 to 700,000 children.

The Ukrainian authorities do not have their own data on the number of deported Ukrainian citizens because they do not control certain sections of the Russia–Ukraine border (and earlier, Ukraine–Belarus border).

According to the UNHCR data, as of 3 October 2022, 2.8 million Ukrainian citizens were transferred to the territory of the Russian Federation, and another 20,900 Ukrainian citizens were in the territory of the Republic of Belarus as of 28 February 2023.

According to the Russian side data, as of December 8, 2022, 5 million people, including more than 700,000 children, arrived in the territory of the Russian Federation from Ukraine.

It is impossible to assess these figures’ reliability and how many citizens were forced to leave under coercion, pressure, and intimidation. But it is evident that deportation is widespread within the overall Russian attack on Ukraine.

Filtration as a prerequisite for deportation

Deportation from Ukraine to Russia is often preceded by a “filtration” process, during which individuals are assessed for their allegiance to the Russian Federation and any collaboration with Ukrainian authorities or military forces. This process can be categorized into three distinct levels.

Filtration measures could be divided into three different levels.

- The first is a quick inspection at checkpoints on the demarcation line or in a particular settlement. During such an inspection, houses, cars, and personal belongings were searched, telephones and computers were examined, fingerprints and photos were taken, and interviews with Russian military personnel (sometimes with the participation of FSB officers) were held.

- The second level involves the primary filtration process, where individuals are taken to filtration centers or camps for thorough inspections and interviews. At these centers, a person may receive a “certificate” confirming they have passed the filtration or may be detained for further examination. People often had to wait in line for days or even weeks to undergo filtration, as they couldn’t leave without a certificate. During the inspection, they experienced psychological and physical pressure, and witnesses have reported cases of Russians executing people by shooting.

- The third type of filtration occurred when the Russians harbored certain suspicions. Those suspected were detained, subjected to brutal interrogation, and held in custody for extended periods. This happened to volunteer drivers who helped evacuate people out of occupied Mariupol. They were transferred to the Olenivka penal facility, and then some were released after 60 to 90 days of so-called “arrest” and offered to leave through the Russian Federation. And some still remain arrested in penal facilities.

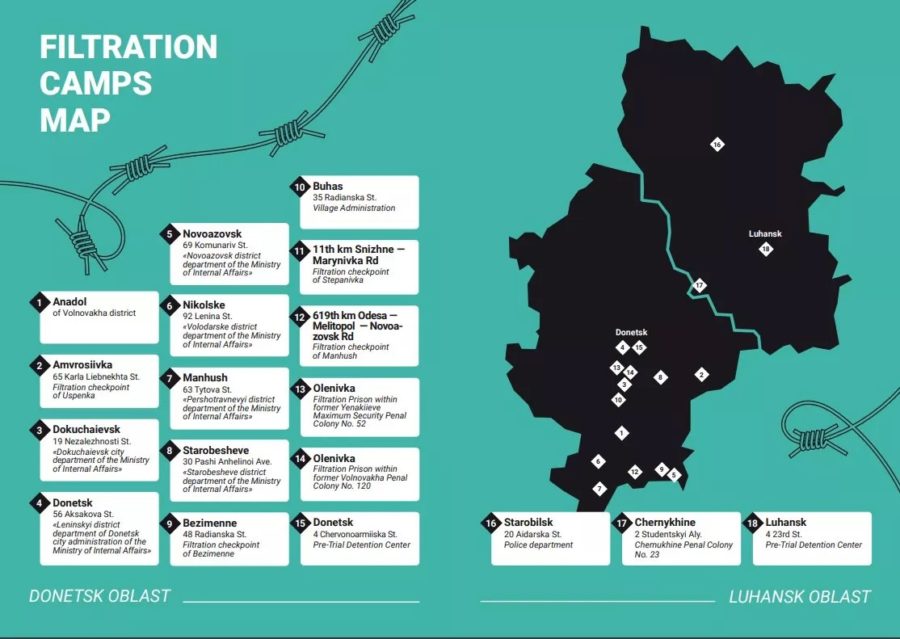

Although filtration measures are taken throughout the occupied territory of Ukraine, filtration camps were mostly located in the occupied territories of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts. According to a Yale HRL report, 21 filtration facilities were identified as of August 2022, in particular in the village of Kozatske (Novoazovsk district), in the village of Vasylivka, and in the villages of Makiivka, Buhas (Volnovakha district), Olenivka (Bakhmut district), Olenivka (Volnovakha district) in the Donetsk Oblast.

Filtration camps in the Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts of Ukraine. Credit: Media Initiative for Human Rights

Filtration camps in the Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts of Ukraine. Credit: Media Initiative for Human RightsIt is in the Donetsk Oblast that the massive filtration process began. There, similarly to the northern regions of Ukraine, the Russian military closed all opportunities to leave the occupied territory and began to actively check citizens: not only those who wanted to go away but also those who were not going to leave their homes.

An atmosphere of fear and intimidation

A characteristic feature of forcible transfer and deportation from Ukraine to Russia is that a person cannot choose where to go.

Coercion is not limited to physical force, such as when someone is forcibly taken into a car at gunpoint. It also encompasses situations in which people are left with no viable options for where to evacuate. Other forms of coercion include threats of violence, harassment, detention, psychological manipulation, abuse of power, and creating a panic-inducing atmosphere. Additionally, limiting access to information and disseminating false information can also be considered forms of coercion.

A temporary facility for Ukrainians in the Russian city of Taganrog. Photo: Taganrog Administration

A temporary facility for Ukrainians in the Russian city of Taganrog. Photo: Taganrog AdministrationFor example, this was the case in Kherson Oblast, where during the occupation, the Russian military seized the Kherson TV tower, replacing Ukrainian TV channels with Russian ones and blocking access to alternative sources of information. The occupiers also shut down mobile communications and the Internet in May 2022, imposing Russian phone operators.

On October 18, the occupation authorities announced a so-called “evacuation.” The Russian mass media spread a statement by Russia’s top army commander in Ukraine, Sergey Surovikin. He alleged that the Armed Forces of Ukraine were preparing to launch a missile strike to destroy the Kakhovka HPP, a claim that Ukrainian authorities denied. Surovikin also declared that Russian troops would ensure the safe departure of residents from Kherson.

Similar scenarios took place in other cities in Ukraine. In particular, ZMINA documented facts of the deportation of residents of border villages in Kharkiv Oblast whom the Russians promised to deport “only for three days” and threatened that “the Armed Forces of Ukraine will come and shoot you all.” Thus, people were forced to get on an “evacuation” bus or get into their cars and drive away. But they could “evacuate” only to Russia or Belarus, as the road to Ukrainian-controlled territory was blocked.

Deportation of custodial facilities from occupied Ukraine to Russia

Custodial facilities such as orphanages and prisons have become targets of deportation by the Russian Federation. The people held in these facilities are particularly vulnerable, as they are restricted in their movements and cannot freely choose to flee the war or decide where to go.

The Russian Federation purposefully prepared to relocate Ukrainian custodial facilities. For example, in some regions of the Russian Federation, penal facilities were vacated to accommodate prisoners from the occupied territories of Ukraine.

For example, inmates of at least four penal facilities were taken from the occupied territory of Kherson Oblast: Hola Prystan penal facility No. 7, Daryivka penal facility No. 10, Kherson penal facility No. 61, and Pivnichna penal facility No. 90. There is also data on the deportation of inmates from Shihurivka penal facility No. 5 from Mykolaiv Oblast. The probable number of deported inmates ranges from 2,000 to more than 3,500.

In addition, Russia relocated Ukrainian children’s institutions and encouraged the childrens’ subsequent transfer to Russian families. According to public information, children from the Novopetrivka Special School, the Oleshky Orphanage, and the Kherson Oblast Children’s Home were taken from the occupied territories of Kherson Oblast.

In reality, Russia has deprived Ukrainian children of the chance to grow and flourish in their own homeland and to return to their families, eradicating their national identity in the process.

The deportation of children from occupied Ukraine to Russia

Children in a camp for deportees in Bezimenne. Photo: Slidstvo.info

Children in a camp for deportees in Bezimenne. Photo: Slidstvo.infoInternational humanitarian law prohibits the transfer of children to other countries due to their vulnerability and limited capacity to make independent decisions. The sole exception is in cases of urgent health-related reasons. The occupying power is obligated to support and not impede the functioning of institutions responsible for the welfare of children in the occupied territory.

The relocation of children’s institutions to the Russian Federation began even before the full-scale invasion of 24 February 2022 on the Ukrainian territories that Russia occupied before that. After the full-fledged invasion started, this process became massive. And its organization was not complicated: the mechanism and occupation infrastructure had already been formed over a long period of time.

Another method of transferring children from Ukraine is sending them to children’s camps for “resting,” a common practice in Ukraine and Russia. The Russian side uses the vulnerable state of the parents, their desire to protect their children from shelling, and the difficulties of life under the occupation, misleading them about the nature and duration of such “recreational activities.” Following the end of each camp shift, Russia typically fails to return the children to their parents, extending their stay on various pretexts, such as the risk of shelling or due to their pro-Ukrainian views.

Camps are also used for “re-education.” During their stay in the camps, the children are offered training and a cultural program based on Russian propaganda. Since last autumn, they have been studying according to Russian education standards. False information about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is imposed on the children, as well as “patriotic education,” accompanied by the militarization of education.

All these measures are carried out at the initiative and with full support from the political leadership of the Russian Federation.

If deportation is a war crime and a crime against humanity, then when it comes to children, their transfer to an aggressor state has the characteristics of a genocidal crime.

In particular, the Ukrainian identity of children is being destroyed due to immersion in the Russian education system, placing children under the care or guardianship of Russian families instead of finding their relatives in Ukraine. And the Russian adoption procedure itself provides for the closure of information about a child, and new parents can change their personal data.

This means that Ukraine will hardly ever be able to find and return the kidnapped children. This already happened in 2014 with children who lived in orphanages in occupied Crimea.

On 21 March, Ukraine returned 15 more children who were deported to Russia. Photo: Ombudsman of Ukraine’s office

On 21 March, Ukraine returned 15 more children who were deported to Russia. Photo: Ombudsman of Ukraine’s officeBringing Russian criminals to responsibility

The crime of deportation must not go unpunished. The Prosecutor General’s Office informed Human Rights Centre ZMINA that they had opened 90 inquiries into illegal transfer within the country or deportation abroad of Ukrainian children.

The International Criminal Court in The Hague is also investigating the illegal deportation of Ukrainian children to the territory of the Russian Federation, and an arrest warrant has been issued for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian Children’s Rights Commissioner Lvova-Belova. The ICC alleges that both individuals are responsible for committing war crimes, specifically the unlawful deportation and transfer of children from occupied areas of Ukraine to Russia.

Citizens who became victims of deportation and were able to return to Ukraine can file a report with Ukrainian law enforcement agencies. If the deported Ukrainians are in the territory of third countries, they can also report this crime to the local authorities. Many countries have a mechanism of universal jurisdiction that enables them to investigate crimes committed during the Russian attack on Ukraine.

In addition, there is an opportunity to report the experienced deportation online, mainly through the website warcrimes.gov.ua, launched by the Prosecutor General’s Office together with Ukrainian and international partners.

War crimes and crimes against humanity, in particular facts of deportations, are also documented by NGOs, including Human Rights Centre ZMINA and Ukraine 5 AM Coalition. If you have witnessed or been a victim of deportation or forcible transfer, human rights defenders ask you to write about it at deportation@humanrights.org.ua.

Source: Euromaidan Press

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.