From Mariupol to Tallin via Russia: a family’s journey

Kateryna Mykhailenko’s most heart-rending memory is the sight she saw when she emerged from the Mariupol basement where she had spent three weeks. It was late March 2022; all around were burned buildings, destroyed streets and gutted houses.

“Graves everywhere, in the park instead of flowerbeds, along the roads,” the 33-year-old recalled.

Kateryna and her husband Mykhailo lived in the left bank district of Mariupol, the southern port city on the Sea of Azov. They and their three-year-old daughter Mylana shared a flat with Victoria, Mykhailo’s mother, and Danylo, his younger brother.

Photo courtesy of Kateryna Mykhailenko

Photo courtesy of Kateryna MykhailenkoThe city of 450,000 became the focus of Russia’s full–scale of Ukraine: it is close to the Russian border and the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) controlled by Russian proxies. By seizing it, Russia would control the entire Sea of Azov. The strategic Azovstal steel plant sprawled for kilometres over the family’s district, which was shelled relentlessly in March and April 2022.

On the night of March 2, a projectile hit a house near theirs, shattering all the windows. The Mykhailenko family hid with other residents in the large basement of the house of culture until, on March 6, that was also hit. A fire broke out and destroyed the entire building.

“At first, we thought the Russians were targeting the Azov regiment base, which was not far away… then it became clear that they were deliberately shelling schools, hospitals, a maternity hospital, and the culture house,” Kateryna said.

The people sheltering in the culture house were taken by the Ukrainian military to the building of the left-bank administration. But that too was hit by a projectile a few days later.

“We ran to the next house, to the basement of the store, which was on the first floor,” Kateryna said.

But by mid-March neither volunteers nor soldiers were able to reach the civilian population to provide assistance.

Every time her husband ventured out in search of food, Kateryna did not know whether he would return.

They remained in this basement for three weeks, surviving on sardines found in a damaged warehouse.

Photo courtesy of Kateryna Mykhailenko

Photo courtesy of Kateryna Mykhailenko“From morning to night, we lived in a constant feeling of fear. I woke to the panic that my child would starve to death, and death was all around,” Kateryna said.

On April 4 a fire broke out in the building above them, but the Mykhailenkos had nowhere else to go.

“We just went to bed hoping we would die from smoke inhalation, and it would not be that scary. But it all worked out,” Kateryna recalled.

Two days later, the Russian military came to their basement and said there would be evacuated. People were lined up and led through what remained of what was once a vibrant city of nearly half a million inhabitants.

The Mykhailenkos did not want to join the evacuation and a soldier allowed them to let them go. They tried to get to their house but could not because of the shelling, so headed to a friend’s apartment. For ten days, they planned how to get out.

“It was impossible to go through the territory controlled by Ukraine, it was only allowed to go to Russia,” Kateryna said. “There was an Orthodox church, and a priest took us to Bezimenne [a settlement between Mariupol and the Russian border].”

They spent the night in the Bezimenne school and the next day the same priest took them to Starobesheve, outside Donetsk.

There the Russians began to question them – asking what they knew about the Azov regiment and the military, interrogating them about how they felt about the “liberation” operation.

Women and children were not checked in depth, but all men underwent hours of interrogation.

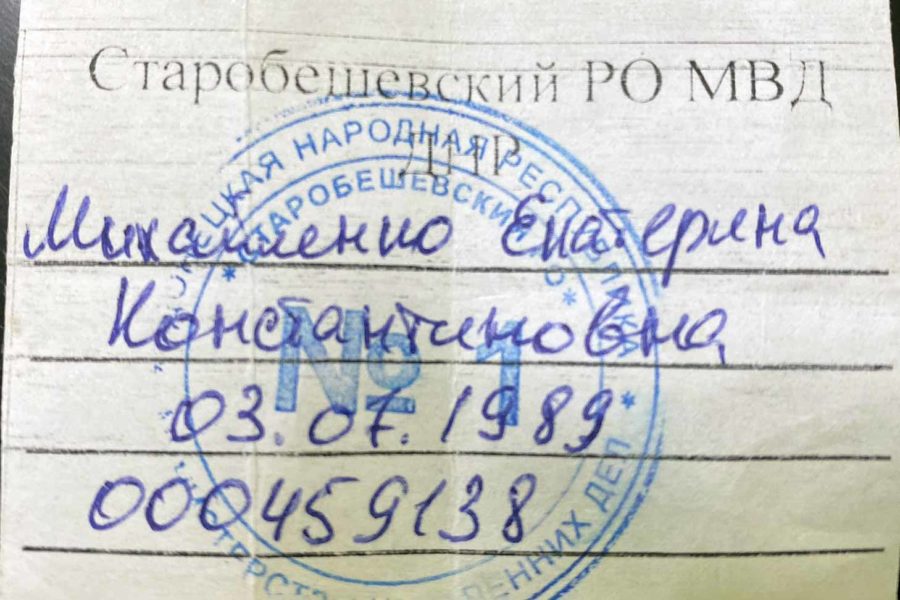

After this, people were given pass cards to move around the occupied part of Donetsk oblast.

A pass card allowing traveling across the temporarily occupied parts of Ukraine’s Donetsk region. Photo: Olesya Lantsman

A pass card allowing traveling across the temporarily occupied parts of Ukraine’s Donetsk region. Photo: Olesya LantsmanIn Starobesheve, the family were offered money to return to Mariupol, go to Donetsk, or travel to the Russian Federation free of charge. As they planned to go to the Czech Republic, they chose Russia.

They were questioned at the border, then offered the chance to go to a refugee centre in Taganrog, in the Rostov region just over 100 kilometres from Mariupol.

“It may be absurd, but we did not shower for two months, did not change into clean clothes, and they offered all this… we agreed,” Kateryna said, recalling that the place was set up in a large gym.

In late April, all residents of the Taganrog centre were told to go to Per, a city deep inside Russia, nearly 1,100 kilometres east of Moscow and double that distance from Mariupol. They were told that a new factory had opened there, and they would have a job, housing and Russian citizenship.

The Mykhailenkos said they had plans to take a train the next day for Khabarovsk, Russia’s easternmost city. Instead, once at the station, they used part of the money they had managed to keep with them to buy tickets for Rostov-on-Don, about 75 kilometres east. From there, they headed north, to St Petersburg.

Friends bought them online tickets to Tallinn, in Estonia, and by the end of April, they had reached the border. They were grilled again by Russian border guards.

“They interrogated us and, of course, inspected our phones. They checked my husband’s knees, to be certain he was not a sniper [who can be identified from bruises on their knees and chest from recoils]. I have a tattoo with spikelets [ears of wheat are one of Ukraine’s symbols] , and if I were examined, we would not have gone further,” Kateryna said.

From Tallinn, the family took a volunteer bus to Warsaw. They settled in Prague in the Czech Republic, where Mykhailo had work, but this meant that the family could not get refugee status. Since his wage was not enough to support them, they decided to return to Estonia.

Since June 2022, the Mykhailenkos have rented a one-room apartment in Rapla, a town 53 kilometres south of Tallinn. Mykhailo managed to find a job, while Kateryna is focusing on learning Estonian.

Life is peaceful now, but memories of the city they had to flee from remain painful.

Source: Institute for War and Peace Reporting

This publication was prepared under the “Ukraine Voices Project” implemented with the financial support of the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO).

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.