ICC arrest warrant for Putin: what’s next, and do we still need a Tribunal? Human rights defender answers

On 17 March, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian Children’s Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova, alleging they are guilty of the war crime of unlawful deportation and transfer of children from occupied areas of Ukraine to Russia. How soon will they end up in the Hague and how does this impact Ukraine’s plan for a special Tribunal against the Russian leadership? We talked to Tetiana Pechonchyk, head of the board of the Zmina human rights NGO, part of the “5 AM coalition” of 31 organizations that collect proof of Russian war crimes, to find out.

Source: LithuaniaMFA/ twitter

Source: LithuaniaMFA/ twitterEP: What is the significance of today’s decision of the International Criminal Court?

Tetiana Pechonchyk: This is a historic decision because it is the third time in the history of the International Criminal Court that an arrest warrant has been issued for a sitting head of state. Previously, it happened only to the President of Sudan, Omar Al-Bashir, for the genocide in Darfur and Muammar Gaddafi for crimes against humanity committed in Libya. And, of course, for all Ukrainians, this is a very big hope that justice, which we often talk about, is not merely a ghost or illusion; this is a very concrete big step towards achieving it.

EP: How did this decision become possible, what evidence was presented, who presented it, and what was the role of civil society, in particular the Five AM Coalition?

Tetiana Pechonchyk: The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Karim Khan, recently announced that they are investigating two cases. One was about the deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia, and the other was about shelling Ukrainian civilian infrastructure. And now, a warrant has finally been issued in the case of the deportation of children, and the suspects are Maria Lvova-Belova and Vladimir Putin.

The Five AM coalition, including our leader, the Regional Center for Human Rights, was dealing with the issue of deportation of children and genocide. We qualified this as genocide, because along with the deportation of children, their national identity was also erased, they were forcefully adopted into Russian families, etc. And our partners submitted materials to the International Criminal Court in October about the deportation of children, in which it was stated that it was Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova who were personally responsible for the war crime of illegal deportation of Ukrainian children from the occupied territories.

Filtration/deportation camp in occupied Crimea. Photo: so-called “Ministry of Information of Crimea”

Filtration/deportation camp in occupied Crimea. Photo: so-called “Ministry of Information of Crimea”I think that all the work of civil society and law enforcement agencies contributed to this decision, through their cooperation with the International Criminal Court. The ICC has always been criticized taking a long time with their investigations, but we see that actually a year after the start of the large-scale Russian invasion we already have the first suspects. And it’s not just anybody, not some generals, not some commanders, but Russian President Vladimir Putin himself.

EP: What will be the further consequences of this decision for Putin and Lvova-Belova? Can we really expect them to be arrested if they leave Russia?

Tetiana Pechonchyk: They should be arrested and brought to the ICC if they enter the territory of one of the 123 countries in the world that have ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

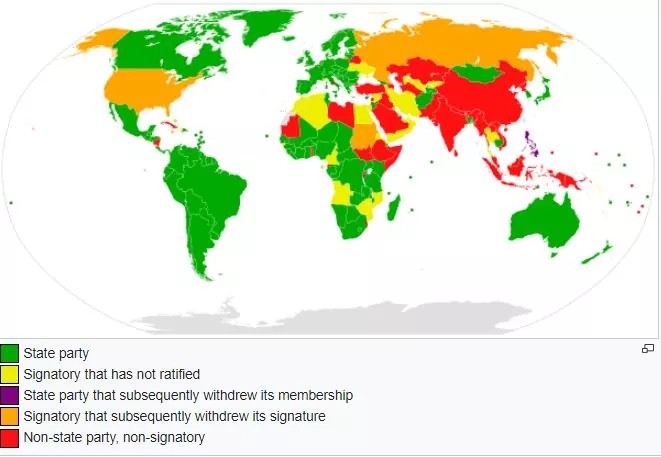

123 states are currently party to the Rome Statute. Image: Wikipedia

123 states are currently party to the Rome Statute. Image: WikipediaThat is, most of the countries in the world are closed to them. This includes all of Latin America, half of the African countries, all of Europe, Canada, and Mexico. The United States of America has not ratified it, but I don’t think the Russian president will go there.

So we can say that, in fact, two-thirds of the world have become closed to the Russian president’s travels. And of course, he will be in the status of a suspect, which is very stigmatizing. This all means that he becomes even more untrustworthy to the rest of the world. And interestingly, this decision of the International Criminal Court to arrest Putin and Lvova-Belova came just before the visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Russia. I think this could also be a signal that China should not get too close to Russia.

EP: What are the implications of the fact that neither Russia nor Ukraine has ratified the Rome Statute? Does this have any consequences for the decision?

Tetiana Pechonchyk: Yes, we have already seen statements today from Maria Zakharova, the spokesperson for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that, in fact, Russia does not recognize this decision because they have not ratified the Rome Statute, claiming that Russia is not subject to the jurisdiction of this court, and its decisions are null and void from the point of view of the law.

But in this case, it does not matter whether Russia has or has not ratified the Rome Statute, as this is a criminal court, which does not concern the responsibility of the Russian authorities as a country; it deals with the responsibility of individuals who may have committed certain crimes that fall within the mandate of this court: war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide.

And the second important point is that there is no diplomatic immunity before this court. Because it doesn’t matter who this suspect is, whether it’s a private soldier, a commander, or even a person who enjoys diplomatic immunity from prosecution.

For example, Ukraine cannot prosecute or imprison Vladimir Putin under its own laws because he, and, for example, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov, is protected by diplomatic immunity. However, this diplomatic immunity does not apply in the international criminal court, even if it is a head of state: the ICC is a court of individual criminal responsibility of individuals, even if it’s the president.

So, Putin’s citizenship does not matter. Regardless of whether the Russian Federation has or has not ratified the Rome Statute, he is a suspected criminal. But it is important for the International Criminal Court to have jurisdiction over the territory of Ukraine, where the crimes in question were committed.

It would be very important for Ukraine to ratify the Rome Statute, which unfortunately has not happened. Nevertheless, the ICC has jurisdiction over Ukraine. This is because there is one exception to the Rome Statute, which states that the court can obtain jurisdiction over a certain country and territory even if they did not ratify it — paragraph 12, part 3 of the Rome Statute. This is what Ukraine did in 2014, and since then, the International Criminal Court has had jurisdiction over all crimes committed there, including the occupied territories and Crimea.

So, although Ukraine does not enjoy the rights of countries that are full-fledged parties to the Rome Statute because it did not ratify it, the ICC has jurisdiction here.

EP: The ICC has prioritized two war crimes — the deportation of children and the bombing of civilians — for which it issued arrest warrants. What about other war crimes? Will there be more cases and suspects?

Tetiana Pechonchyk: I expect there will be others. There may be a range of suspects, including President Vladimir Putin, as well as other top Russian officials and military officers. The International Criminal Court focuses on war crimes cases involving those with the highest possible positions. They aim to unravel the chain of command and find evidence of who gave commands at the highest level to punish those who are responsible.

Regarding the more than 70,000 Russian war crimes registered by Ukraine’s Prosecutor General’s Office, the ICC is investigating only a small part of them as its own cases. They have announced two cases, and a suspect has been named in one of them. There may be five or ten more cases announced, but no more. This means that the remaining tens of thousands of war crimes will be investigated by national authorities, including the police, the prosecutor’s office, and Ukrainian courts.

EP: How soon can we expect a court decision?

Tetiana Pechonchyk: It is difficult to say. The International Criminal Court has an important characteristic where it only considers cases when suspects are physically arrested and brought to the court with their own lawyers to represent their interests. Until Putin and Lvova-Belova are physically arrested and brought to the ICC, the court won’t begin to consider the cases.

This means that we don’t know if it will take years, decades, or it will happen faster, or when Russia will collapse. This is unlike Ukrainian law, where in absentia procedures are possible, and cases can be heard and judgments passed in the absence of the suspects. However, the ICC does not allow this, so the trial won’t begin until Putin is physically arrested.

EP: What about the special tribunal? Why is it needed, and will it exist?

Tetiana Pechonchyk: The International Criminal Court deals with four types of international crimes. These are:

- war crimes

- crimes against humanity

- the crime of genocide

- the crime of aggression.

But in the Ukrainian situation, only the first three types of crimes can be applied, not the crime of aggression; in principle. it falls under the jurisdiction of this court, but due to a number of jurisdictional restrictions, it does not apply in the case of Ukraine.

It turns out that this court can consider cases that are the consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it cannot do anything about Russia’s attack on Ukraine itself, which is also one of the most serious crimes against peace.

And that is why work was initiated to create a separate special tribunal for the crime of Russian aggression against Ukraine, for which the top Russian leadership, which unleashed this war that began not a year ago but back in 2014, should be held accountable.

The International Criminal Court itself was not very favorable to creating another such tribunal. And Karim Khan has repeatedly commented publicly that he believes it will distract attention and take resources away from the IICC itself.

I don’t quite agree with that because, in fact, the crime of aggression is the source of all other crimes. If there had been no Russian attack on Ukraine, there would have been no torture, no enforced disappearances, no deportations, and no other crimes.

And so it turns out that we are investigating these secondary crimes and trying to prosecute the perpetrators, to punish them, but simply because Russia attacked Ukraine, we do not take anyone in. That is, we remain outside all existing accountability mechanisms.

That is why, for example, our organization issued a statement a year ago, signed by many other NGOs, saying that a special tribunal for the crime of aggression is needed.

The Ukrainian state and Ministry of Foreign Affairs did a great job convincing other countries that such a tribunal is needed. This work was also possible, given that we did not know whether the International Criminal Court would ultimately recognize Putin as a suspect in any of the cases. There was a risk that it might not, like in the situation [with Russia’s war against Georgia in 2008], where arrest warrants were issued against three officials from South Ossetia, but no Russians were prosecuted in any way.

If we are talking about a special tribunal for the crime of aggression, it is obvious that one of the main suspects would be Russian President Vladimir Putin, who started this aggressive war.

That is why, from this point of view, the work on creating such a tribunal was carried out and is still ongoing.

However, the fact that the International Criminal Court has issued an arrest warrant for Putin is a strong counterargument to this big advocacy campaign for creating a tribunal for the crime of aggression.

Because someone might ask why you need another court to punish Putin if there is the ICC, which has issued an arrest warrant for him. And this can also be an argument, although I believe we must strive to ensure that all international crimes are addressed. If there are no separate mechanisms, special or tribunals, for some of them, then they should be created.

Source: Euromaidan Press

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.