Legislation on collaborationism does not comply with international humanitarian law and persecutes those trying to survive the occupation

Ukrainian legislation on responsibility for collaborationism does not take into account the norms of international humanitarian law and persecutes Ukrainians who perform vital functions while under occupation, such as housing and medical work. The legislation still does not clearly state what activities the state can prosecute citizens for during the occupation.

Photo: Ukraine Crisis Media Center

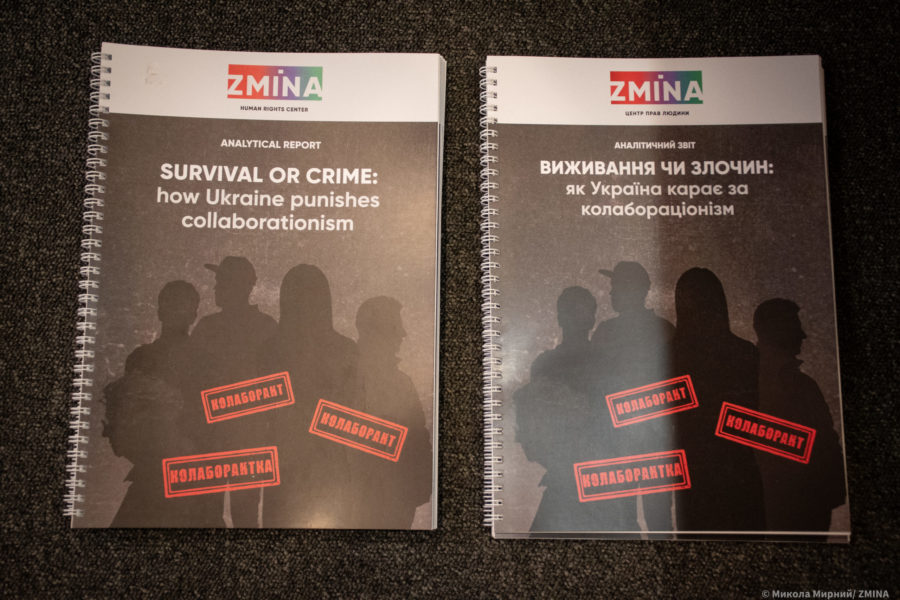

Photo: Ukraine Crisis Media CenterThis was announced on July 30 by representatives of the Human Rights Centre ZMINA during a press conference where they presented the report “Survival or Crime: How Ukraine Punishes Collaborationism“.

As of June 15, 2024, according to the Security Service of Ukraine, 9,179 criminal proceedings were registered under Article 111-1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (“Collaborative Activities”). In the Unified State Register of Court Decisions, there are 1,442 verdicts in cases under Article 111-1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, and the largest number of them (484) are verdicts under the first part of Article 111-1 – on public denial of Russian aggression.

“A third of the sentences relate to public denial of Russian aggression, 90% of these sentences are about insults and posts in Odnoklassniki.” The number of sentences under more serious articles is increasing, such as punishment for voluntarily taking positions in the administrations of the occupiers or judicial and law enforcement bodies, but the majority of sentences are still handed down under Part 1 of Article 111-1 of the Criminal Code, and this shows that the focus remains on the easiest cases to investigate,” comments Legal Analyst of the Human Rights Centre ZMINA Onysiia Syniuk.

In addition, the Register contains 11 cases concerning employees of the State Emergency Service and 18 cases concerning employees of communal institutions. According to Syniuk, the Ukrainian legislation on collaborative activities does not comply with international law, because it persecutes those who help maintain the basic conditions for life in the occupation.

Onysiia Syniuk / Photo: Ukraine Crisis Media Center

Onysiia Syniuk / Photo: Ukraine Crisis Media Center“That’s why lawmakers should provide for a clear distinction between actions that support life in the occupied territory and actions that threaten national security,” Syniuk adds.

The expert says that law enforcement officers and judges hardly investigate whether the suspect had the intention to harm national security, and do not take into account the atmosphere of coercion and intimidation in the occupied territory. The human rights activist also drew attention to the fact that if the accused is present at the trial, the probability of a milder punishment is greater. At the same time, Sinyuk notes that currently there are almost no acquittals – there have been only two in total since 2022.

Currently, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine has registered at least 16 draft laws related to collaborationism, but most of them do not solve the problems pointed out by human rights defenders. Moreover, nine draft laws propose strengthening criminal liability for cooperation with the enemy.

“However, none of these draft laws have been adopted so far. This is connected, in particular, with the lack of political will or the opinion that these decisions are not on time. But while the state does not solve the problems in the legislation, the population of Ukraine under occupation is becoming more and more distant from us due to the awareness that the legislation may consider them collaborators,” notes Inna Vyshnevska, a Research Associate of the research laboratory of the Lviv State University of Internal Affairs.

Inna Vyshnevska / Photo: Ukraine Crisis Media Center

Inna Vyshnevska / Photo: Ukraine Crisis Media CenterZMINA’s researchers also evaluated how the topic of collaborationism is conveyed to society through journalistic materials and messages from state authorities. The Semantrum monitoring platform commissioned by ZMINA analyzed 339,536 publications in Ukrainian media of various types and 25,268 publications on websites and pages of state bodies.

As the monitoring showed, 49% of messages from law enforcement agencies contained clear negative words about people accused or suspected of committing crimes. For example, the word “criminal” is the most frequently used for suspects or those convicted. Moreover, most of these publications – 43%, do not have information about the verdict, and 35% of publications with photo materials did not contain face blurring. At the same time, in media materials, the percentage of publications with clear negative vocabulary is somewhat lower — 42%. Additionally, 39% of these publications do not have information about the suspect’s conviction, which can be a marker of violation of the presumption of innocence. In addition, articles and reports on the topic of collaborationism often have an emotionally coloured tone: expressions such as “traitor”, “collaborator”, and “selling skin” are used, which emphasizes the negative attitude towards such people and their actions.

“The highest level of negative words, both in law enforcement agencies and in the media, is observed in frontline regions or where hostilities took place. But we did not find a special policy of state bodies or the media to cover this topic negatively or, on the contrary, strive to adhere to standards. Most sources post both correct materials and materials with markers of a possible violation of the presumption of innocence,” comments Veronika Volkovynska, Head of the Department for the Semantrum Platform.

Also, according to representatives of ZMINA, the state policy of punishment for collaborationism should take into account the opinions of communities that were under occupation or are still occupied. The researchers conducted facilitated discussions in the communities of Chernihiv, Sumy, Kharkiv, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia regions and found, in particular, that the residents of these communities seek proportionate punishment of collaborators relative to their actions. Residents of the communities believe that those who helped the occupiers establish power should be unequivocally brought to justice; who worked in enemy administrations or organized referendums, and elections; who worked as law enforcement officers or “enforcers”; who deliberately spread the propaganda of the Russian Federation; who voluntarily provided the occupiers with information about pro-Ukrainian citizens, etc.

At the same time, the interviewed residents say that people should not be punished for the fact of living in the occupation; for obtaining a passport of the Russian Federation, if it is necessary for survival; for receiving humanitarian aid or social benefits, and there should be no punishment for medics and “rescuers” who helped support life in the occupation.

“Interviewed residents had a request for a punitive, criminal format of responsibility, but this responsibility should be commensurate with the person’s actions. Among the participants, we saw both a demand for upholding standards of justice and a low assessment of the system’s ability to deliver it. It is the unrealized request for justice that becomes the driver of the severity and harshness of punishment, and communities are ready to take over these functions if the state does not do it,” said Maksym Yelihulashvili, facilitator, expert of the Ukraine 5AM Coalition and co-author of the report.

Maksym Yelihulashvili / Photo: Ukraine Crisis Media Center

Maksym Yelihulashvili / Photo: Ukraine Crisis Media CenterThe text of the report is available at the link.

Watch the video broadcast from the event here.

This event took place with the support of the Partnership for a Strong Ukraine Fund, which is financed by the governments of the United Kingdom, Estonia, Canada, the Netherlands, the United States of America, Finland, Switzerland, and Sweden.

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.