Human rights defenders spoke about foreign political prisoners in Belarus, which includes Ukrainian prisoners

On January 31, the office of the Democratic Forces of Belarus in the Czech Republic hosted a discussion titled “Lines Crossed, Freedom Lost: Persecution of Foreigners in Belarus”. The event was attended by Belarusian and Ukrainian human rights defenders, including representatives of the Human Rights Center ZMINA as well as foreign diplomats.

Natallia Hershe, a former Swiss political prisoner, opened the event. She spoke about her life in prison, including her time in the punishment cell: to keep warm, she jogged in place and stomped her foot on the floor so hard that she broke her leg.

“In the workshop of Gomel Correctional Colony No. 4, where I worked with other women, the walls were painted with oil paint. One of the women fainted from the strong smell. The guards took her out into the fresh air, but after a short time they brought her back to work and she fainted. After that, the woman was taken to the hospital by ambulance. She did not come to work for two weeks and then walked with a cane out that she had suffered a brain haemorrhage and would remain disabled for the rest of her life,” Natallia recalls.

Since 2020, at least 75 foreigners have been subjected to political repression in Belarus. Currently, 38 foreign nationals are imprisoned, including 36 officially recognized political prisoners, according to the Viasna Human Rights Center.

There are at least thirteen Ukrainians, eight Russians, four Poles, four Latvians, two Englishmen and one prisoner each from Lithuania, Estonia, the United States, Japan and Sweden. Additionally, one of the Latvian prisoners was sent for compulsory psychiatric treatment. The list of political prisoners also includes one foreigner whose citizenship is unknown.

Victims of politically motivated persecution are accused of “agent activity”, “terrorism” (such cases have been actively brought since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine), “insulting Lukashenko”, “insulting the authorities” and “inciting hatred”.

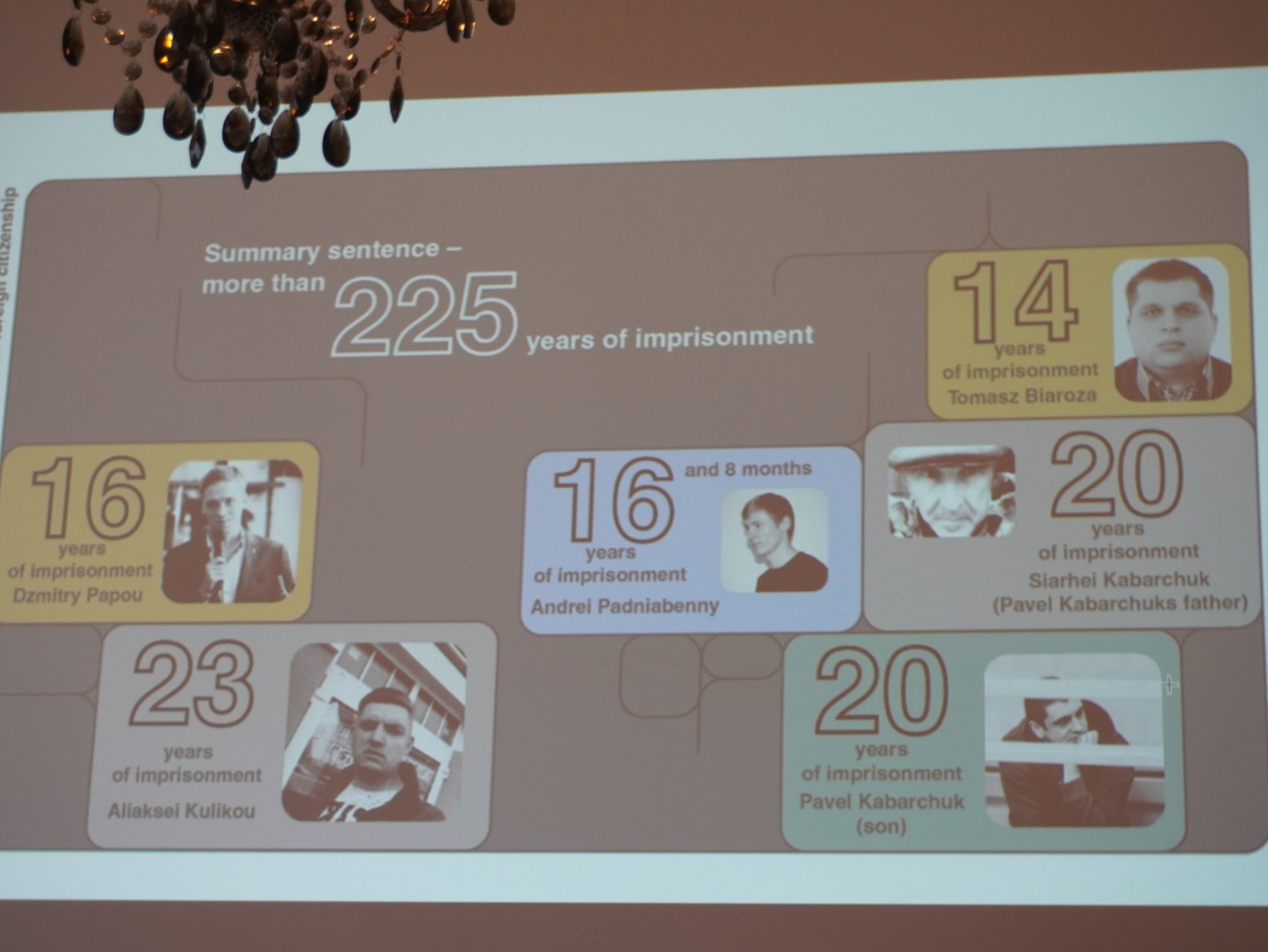

In total, foreign political prisoners collectively received at least 225 years in prison. Some sentences are particularly harsh, for example, Ukrainians Serhii and Pavlo Kabarchuk, father and son, were sentenced by the Gomel Regional Court to 20 years in a high-security penal colony. Pole Tomasz Biaroza was sentenced to 14 years in prison for “agent activity”. The most severe sentence – 23 years – was handed down to Russian Oleksii Kulykov for photographing military facilities and the Russian Consulate General in the Belarusian city of Grodno. His final words in court were spoken in Ukrainian.

In addition, in 2024, Belarus released a propaganda film “Children in the Crosshairs. Recruited by the Enemy”, which reported on the detention of seven teenagers for “cooperation with the Ukrainian special services”. The film said that the teenagers allegedly united in the anarchist organization Black Nightingales, which was created by 16-year-old Ukrainian citizen Maryia Misiuk “under the leadership of the National Liberation Army of Ukraine”. The children are accused of an “act of terrorism”.

There is precedent for the release of political prisoners from Belarusian custody. In particular, five Ukrainian citizens were released in exchange for Russian prisoners of war. German Rico Krieger, who was sentenced to death in Belarus, was also handed over to Germany as part of a major exchange when Russian FSB officer Vadym Krasikov was released from a German prison.

Recently, Lukashenko has also “pardoned” several hundred Belarusian political prisoners, while still keeping more than a thousand in illegal detention. Media expert Anna Liubakova emphasizes that the release of political prisoners does not mean their complete freedom, and this should also be taken into account when covering the waves of “pardons”. Additionally, those released often cannot return to normal life: they are still being monitored by the security forces, and many cannot find work or leave the country. Sometimes, they are even attempted to be recruited to cooperate with the KGB RB (not to be confused with the former USSR KGB) or are arrested again.

At the same time, everyone can contribute to the release of political prisoners from Belarusian captivity. Human rights defenders urged people to share the stories of those behind bars, send requests for information about their whereabouts and health, mentor them and write letters.

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.