Trials of Ukrainian civilians and prisoners of war in Russia and occupied territories are a war crime – human rights defenders

Russia systematically denies arbitrarily detained Ukrainian civilians and prisoners of war the right to a fair trial. This practice has reached an alarming scale and has become an instrument of persecution.

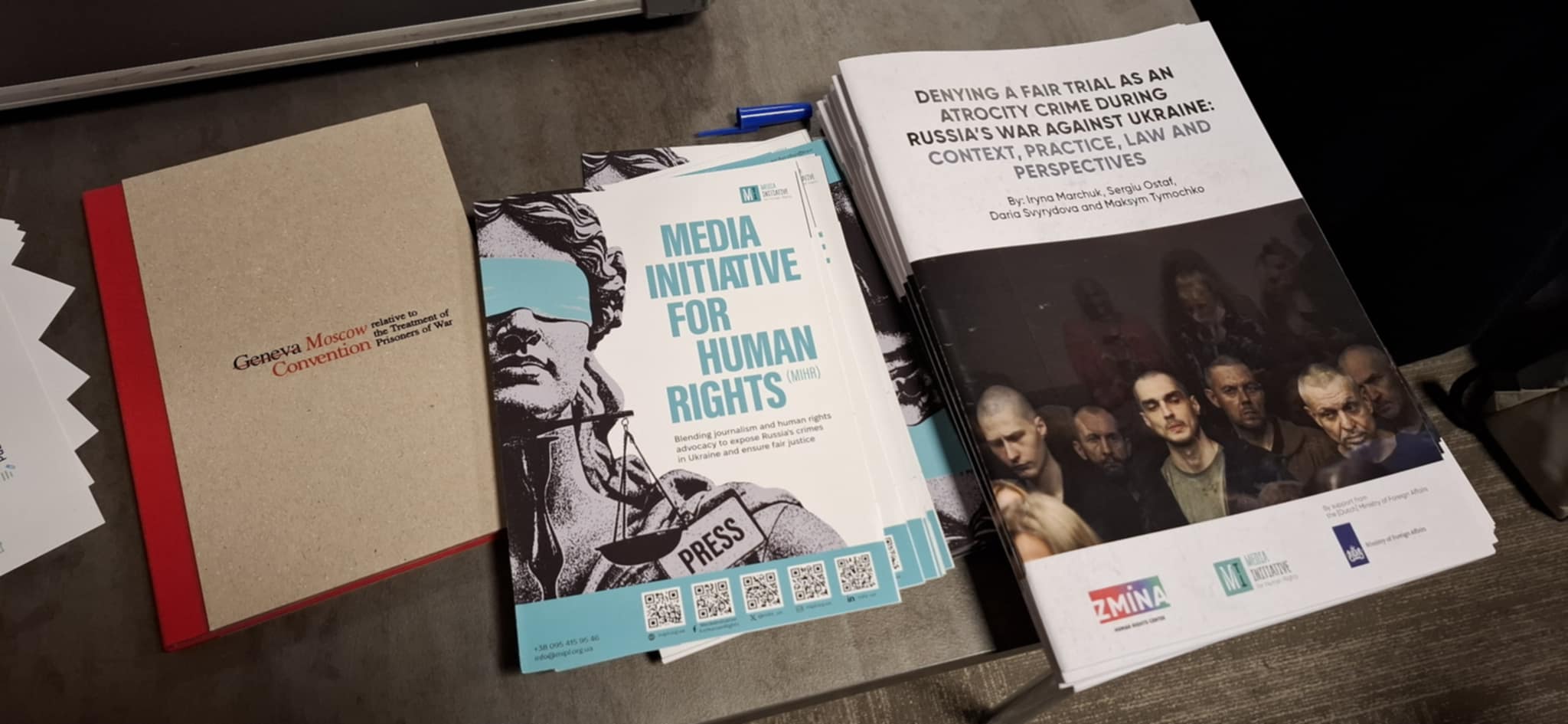

Photo – Iryna Drabok

Photo – Iryna DrabokThis was stated by Ukrainian human rights defenders in The Hague during a special event within the framework of the Assembly of States Parties to the International Criminal Court, where they presented the key findings of a study prepared by the Human Rights Centre ZMINA and the Media Initiative for Human Rights in cooperation with the Hraty publication and the Crimean Process initiative.

This study continues the analytical work on politically motivated trials of the Russian Federation against Ukrainians, which began in 2018 on the material of monitoring of the Crimean occupation courts. However, the new study proves that in the context of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the denial of a fair trial can be qualified not only as a human rights violation but also as a war crime and a crime against humanity. It is important to note that the requirement for a fair and just trial is one of the fundamental principles of the Geneva Conventions.

Photo – Iryna Drabok

Photo – Iryna DrabokThe new study is based on materials collected in Russian courts and in the occupied territories, including Crimea.

“Together with partner organisations, including the NGO Crimean Process, we monitor trials and collect information about Russia’s crimes in the occupied Crimea in trumped-up criminal cases, including politically motivated cases. For the purposes of this study, 84 court hearings were monitored in Crimea in 26 cases on charges of terrorism, extremism, participation in illegal armed groups, illegal possession of weapons, sabotage, espionage and treason,” said Viktoriia Nesterenko, Project Manager of the Human Rights Centre ZMINA.

According to her, in 2024, the number of cases related to “treason” (Article 275.1 of the CC of the RF) in Crimea increased to 33. For comparison, before 2021, there were no such cases in Crimea at all, and in 2021 and 2022, only one case was considered per year.

Nesterenko added that in some cases it was difficult to get access to the court or any information about the process, as almost half of the court hearings and verdicts take place behind closed doors. She also noted that over the past two years, Russia has been trying to conceal information as much as possible, not publishing court decisions and removing old decisions from official court websites. This applies not only to the occupied Crimea but also to the rest of the Russian courts.

Photo – Iryna Drabok

Photo – Iryna DrabokOlha Reshetylova, Head of the Media Initiative for Human Rights, also spoke about the difficulties in the work of researchers: “It is expected that since the beginning of the full-scale war, the number of cases against civilians and prisoners of war has increased significantly. With the formal annexation of the occupied territories, Russia began to integrate them into its legal framework. Comprehensive monitoring of the trials conducted by Russia against Ukrainian civilians and prisoners of war is either extremely difficult or impossible due to the risks to the freedom, life and health of observers. Together with experts Iryna Marchuk, Daria Svyrydova, Sergiu Ostaf and Maksym Tymochko, we have developed a methodology that would allow us to combine statistical research methods with qualitative analysis of specific cases to which we have access.“

Thanks to the partner publication “Hraty”, the monitoring results of 20 cases were handed over to experts for processing. In addition, open sources were studied, in particular regarding the situation with courts in the temporarily occupied territories.

Photo – Iryna Drabok

Photo – Iryna DrabokSergiu Ostaf, Director of the Resource Center for Human Rights (Moldova), spoke about the statistical and qualitative methods used to prove the crime of persecution of Ukrainian citizens.

“ZMINA and MIHR impressed with the first massive data from open sources – about 600 cases against Ukrainian civilians and military. They are being prosecuted by “courts” in the occupied territories and in Russia. This database is likely to be only a part of thousands of cases against Ukrainian civilians and military personnel detained by the Russian authorities since February 2022,” Ostaf emphasises.

According to him, the research team used a combination of statistical methods and legal qualitative analysis: “We randomly selected a representative dataset of approximately 30 cases and observed the relevant court hearings.“

In total, there were around 150 trial observations based on approximately 40 criteria of what a fair trial should be. In addition, about ten cases were subject to in-depth legal qualitative analysis, including verdicts, indictments, etc.

“The team came to a firm conclusion, based on evidence, that there are systematic and ongoing violations of fair trial guarantees. We are talking about the lack of openness of courts, equality of parties, the right to defence, justification of court decisions, presumption of innocence, etc,” said Ostaf.

Iryna Marchuk, Associate Professor of International Criminal Law of the University of Copenhagen, spoke about the illegal activities of Russian judges and prosecutors, which have become systemic.

“Among those who commit all these crimes against Ukrainians in Russia and in the territories it occupies are prosecutors, judges and, probably, officials of the Russian Ministry of Justice and other occupation authorities who give orders and instructions to judges and prosecutors. Their actions are no less serious than those who torture victims or subject them to other inhumane treatment, as they legitimise further violence against victims who are sentenced to long prison terms, often in maximum-security penal colonies,” she said.

Marchuk emphasised that the International Criminal Court should recognise the horrific nature of the crime of denial of a fair trial and prioritise the investigation of this crime on the same level as torture and other crimes committed by Russia in places of illegal detention.

The study will be made public in early 2025. On its basis, human rights defenders will prepare a submission to the International Criminal Court.

The event was organised with the financial support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.