Epidemic of attacks on activists in Ukraine – result of aborted police reform

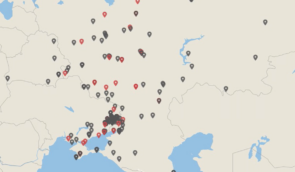

Since 2017, over 55 activists and politicians have been attacked in Ukraine. Many observers are seriously worried about this. What’s up with the attacks and why are they piling up just recently? We examine why in this article which was first published in German on Ukraineverstehen.de.

On 15 October, Daryna Aleksandrova heard her car alarm go off on 3 AM. It was too late – the two cars of the family were burned to the ground. Aleksandrova, a young member of the city council of Kotsyubynske, a satellite of Ukraine’s capital Kyiv, said that the arson was connected to her attempts to break corruption schemes and to preserve a nearby forest.

Aleksandrova’s burned cars. Photo: National Police

Aleksandrova’s burned cars. Photo: National PoliceThe news did not surprise anyone in Ukraine. Three weeks ago, at the opposite side of the country, in the seaside city of Odesa, doctors had barely managed to save the life of Oleh Mykhailyk. The 43-year old activist and leader of the young political party “Syla Liudei” was shot in the chest when returning home.

His party members are sure that the attack was connected to Mykhailyk’s campaigns against illegal construction – and to Odesa’s scandalous mayor Hennadiy Trukhanov, who still manages to keep his position despite ample proof of corruption – and a Russian passport, which is forbidden by Ukrainian law.

Oleg Mykhailyk (holding the loudspeaker) was a visible figure in Odesa’s political life. Photo: Pravda.com.ua

Oleg Mykhailyk (holding the loudspeaker) was a visible figure in Odesa’s political life. Photo: Pravda.com.uaThese two attacks on civic activists in Ukraine are the latest of at least 55 since 2017, and it’s seriously starting to worry civic society in Ukraine. Over 50 NGOs signed a joint appeal comparing the current situation of “persecution of public activists and inaction of the state“ with the days of ex-president Yanukovych – and calling on the government to finally investigate the attacks.

In response, Prosecutor General Lutsenko suggested that the activists themselves were guilty for the attacks, by being too critical of the government.

More active citizens – more attacks since Euromaidan

Tetiana Pechonchyk, head of the Human Rights Information Center, thinks the situation is actually worse than in Yanukovych’s days: the number of attacks on activists has actually grown since the Euromaidan revolution.

There are several explanations, she says.

- First, the post-Euromaidan outburst of civic activity throughout the country, especially in the regions, has led to more active citizens who get involved in the processes of decentralization, form unions to address issues of illegal construction, destruction of parks, and otherwise participate in public life. This all interferes with the existing corruption schemes of local authorities.

- Second, Russia’s undeclared war in eastern Ukraine has raised the levels of violence – and tolerance to violence. In some cases, the hitmen of the attacks were veterans of the war, who have no state programs to help them reintegrate back to peaceful life.

This explains why, according to Pechonchyk, the victims come from three tribes: the anti-corruption activists, “environmental” activists in the wide sense – who protest deforestation, destruction of parks, illegal construction etc., and LGBT and feminist activists who fall victim to attacks of far-right groups.

“In many cases the law enforcement organs are incapable of conducting an effective investigation, and in some cases, we suspect that they deliberately engage in sabotage. The prosecutorial reform has totally failed, the reform of the police stopped at the ‘façade’ level of the patrol police, but the detectives who must investigate these crimes have not been reformed,” Pechonchyk says.

In the case of Kateryna Handziuk, an activist in the south-Ukrainian city of Kherson who had been drenched with sulfuric acid near her home, the police got active only after a public uproar, which Handziuk’s friends aptly dubbed “butt-kicking democracy.”

Thanks to wide coverage and protests, the case was reclassified from the absurd “hooliganism” to “attempt at murder.” The police even arrested an innocent man, only to extinguish the wave of public anger.

Two and a half months after the attack, the hitmen have been arrested, but the organizer is still unknown – as is the case with the rest of the 55 attacks.

“Who’s behind all these criminals? Who’s covering and protecting the organizer? Why have so many investigations been sabotaged? Why should we put up with this while the most dedicated activists are being killed or crippled? Why should we encourage ordinary Ukrainians to engage in social activities and civic activism if we cannot protect them?”

asks Handziuk in a video appeal from her hospital bed, where she is facing a long recovery from burns to 30% of her body.

Kyiv allows regional elites to rule like feudal lords in exchange for votes

Odesa has become a hotspot for attacks on activists. One of them, Serhiy Sternenko, had been attacked three times in 2018

Odesa has become a hotspot for attacks on activists. One of them, Serhiy Sternenko, had been attacked three times in 2018As there are no effective investigations into the attacks, the ultimate reason for them is unclear. Russian influence in order to cause chaos is often suggested, but there is no proof yet. But Mykola Vyhovskyi from the “Chesno” movement which monitors elections in Ukraine is confident that the attacks have another reason behind them which is no less sinister: there is an unofficial agreement by which President Poroshenko allows local elites to do whatever they want in exchange for their loyalty during elections.

“According to the conditions of the agreement, the local elites ensure the president is reelected [during the 2019 election – Ed], and in return they get immunity. So, the regions are thrown into the lap of the local elites, who can do whatever they want. And activists get into their way, they are pressured or physically destroyed,” Vyhovskyi believes.

In any case, this explains the plethora of attacks on activists in Odesa: while mayor Trukhanov is the most likely suspect according to the organizations of the victims, the police never views him as a suspect, and despite damning evidence of his complicity in violations, Trukhanov is allowed to preside over Odesa as if nothing has happened.

Forced to flee

According to Pechonchyk, many activists were attacked several times. Some are intimidated into leaving the country. Such is the story of Kyiv activist Valentyna Aksionova, who led a campaign to prevent the destruction of a nearby forest. After the arson of her car, inaction of the police, and threats to her family, she was forced to leave Ukraine. As well, LGBT activist Ihor Zakharchenko had in 2017 fled Ukraine after attacks and has now received the status of a refugee.

But at least one thing is better now, says Pechonchyk: at least the state doesn’t use punitive psychiatry against activists like it happened several times before Euromaidan. However, the legal framework for activists has gotten worse: a law obliging anti-corruption activists to reveal their assets on par with state officials is currently enacted, and at least three other laws seeking to limit the activities of civic activists and NGOs are on the table in Parliament.

“These are shocking facts when this centralized offensive and limitation is happening from the side of the authorities,” Pechonchyk says.

Some experts are openly speaking of a coordinated state assault against civic activists.

Will Daryna Aleksandrova with her recently burned-down cars also be intimidated into leaving Ukraine, like Valentyna Aksionova, who was forced to flee after having her cars burned, and her family harassed? This will depend on whether Ukraine’s post-Euromaidan government will occupy itself with finally getting on with a reform of the law enforcement organs or continue its campaign against activists. Unfortunately, the pre-election time Ukraine is entering gives no hope for the first.

Source: Euromaidan Press

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.