Media and Russian aggression: how to find boundary of freedom of speech

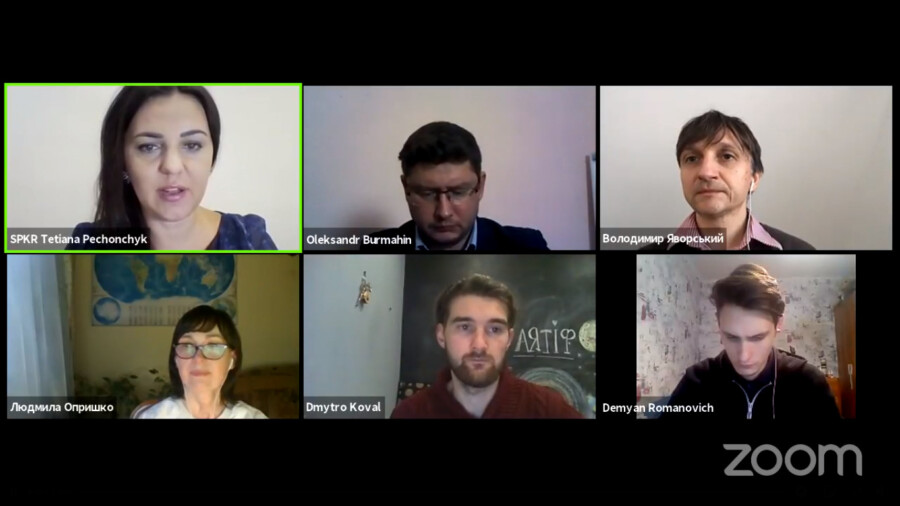

On December 10, online discussion entitled “Limitations to freedom of expression in the conditions of Russian aggression: how to find the boundary?” with the participation of representatives of media and human rights organizations was held within the framework of the annual National Human Rights NONconference.

According to ZMINA Chair Tetiana Pechonchyk, a number of drafts have been registered in the Verkhovna Rada that provide for responsibility for publicly denying the fact of military aggression of the Russian Federation, its occupation of part of Ukraine, Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine, etc.

In particular, these are drafts No.4085 of 14 September 2020 and No.4136 of 21 September 2020 (both authored by MP Yelyzaveta Yasko (Servant of the People party faction) and groups of other MPs), as well as drafts No.4188 of 05 October 2020 and No.4189 of 05 October 2020 (both authored by MP Oleh Dunda, Servant of the People party faction). In addition, similar restrictions on freedom of speech are enshrined in the draft law “On Media” (No.2693 of 27 December 2019).

What are the international standards in the field for freedom of speech and when can restrictions be justified? What is the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) regarding the freedom of speech in the context of armed conflict? How can Ukraine adopt effective and efficient legislation that, on the one hand, will actually bring violators to justice and, on the other hand, will meet international standards in the field of freedom of speech and will not expose Ukraine to new losses in the ECHR? These issues were discussed during the event.

Human rights defender Volodymyr Yavorsky noted that all these drafts raise many questions from the point of view of international law. Moreover, the Criminal Code of Ukraine currently stipulates criminal offenses that restrict freedom of speech. “But in practice, law enforcement agencies hardly apply these articles, although there are many manifestations of freedom of speech that fall under these crimes. Therefore, it may seem that we have bad legislation in this area for countering Russian aggression,” the expert added.

Yavorsky notes that many of the provisions of these drafts, which prohibit or restrict the dissemination of information, provide for liability for evaluative judgments. Such prohibitions are not about disseminating unreliable facts or information, but about assessing those facts. As a rule, it is formulated through such expressions as “propaganda”, “positive coverage”, “popularization”, “positive assessment”, “excessive focus”, etc.

The human rights defender reminds that there are a number of standards that should be taken into account when elaborating such drafts. One of them is the distinction between evaluative judgements and facts. In addition, it is important to assess the proportionality of the punishment for abuse on freedom of speech and to anticipate the gradation of the possible danger of such a violation.

Liudmyla Opryshko, an expert on the Human Rights Platform, is also convinced that approaches to restricting freedom of speech in such drafts should be balanced with other rights. She also agrees that Ukraine already has the necessary tools to combat Russian propaganda, but the state must make efforts to ensure that these tools are actually used. However, she considers all currently proposed drafts are likely to restrict freedom of speech means that are not accepted in a democratic society.

“There are at least 8 articles in the Criminal Code of Ukraine that provide for liability for abuse of freedom of speech. But over the past four years, only 118 sentences have been passed under these articles, and only less than 10 sentences concern Russian propaganda and aggression,” said Oleksandr Burmahin, director of the Human Rights Platform. Also, according to him, the court does not provide in their judgments the explanations or recommendations on what should be done with this propaganda content.

Moreover, according to Burmahin, despite the existing mechanisms for combating pro-Russian propaganda, the state does not have a universal approach to understanding the problem and a clear strategy in this area.

Oleksiy Pohorelov, the President of the Ukrainian Media Business Association, member of the Commission on Journalism Ethics, is convinced that banning the broadcasting of “unpleasant things” in the media deprives people of the opportunity to understand these things at all. “If we close primary source and do not see it in our sources, we will see it on enemy channels, where they will provide information as they want to,” he said.

Watch the full video of the discussion here.

The event is organized by ZMINA, Freedom House Ukraine.

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.