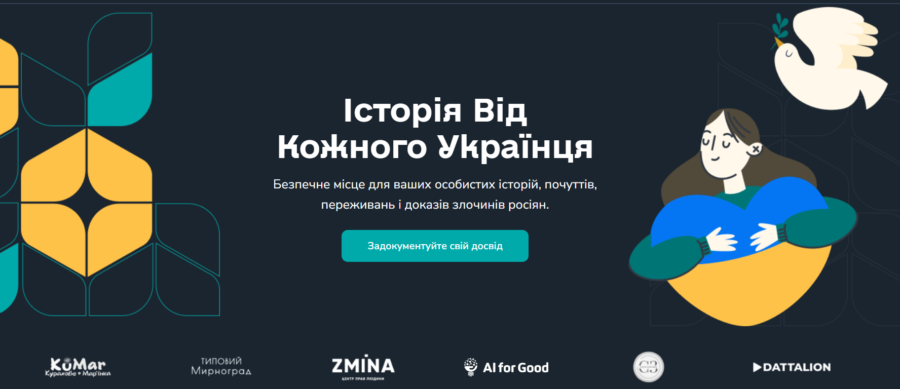

ZMINA and Svidok collect Ukrainians’ testimonies about war

Human Rights Centre ZMINA and the all-Ukrainian online platform Svidok.org have become partners and gather the testimonies of every Ukrainian about the war waged by Russia against Ukraine within a nationwide flash mob.

A unified digital museum of memories of the war, available to the whole world, will be later created based on the posts of Ukrainians.

“The full-scale war changed the lives of each of us, and if it is erased from the nation’s memory, there is a risk that history will repeat itself in the future. The goal of the flash mob is to preserve the memories of every Ukrainian in a safe place, on a platform that, unlike social networks, will not only spread these stories around the world but also preserve them for future generations,” says Olena Kuk, content and communications director of Svidok platform.

Svidok.org is a secure social memories platform where people anonymously describe their life experiences during the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It was created by Ukrainian IT specialists with the support of the AI for Good foundation.

To save your memory, you need to register on Svidok.org or use @SvidokNoteBot Telegram bot. You can then create your anonymous posts: they can be memories of how a person survived shelling, witnessed destruction, was injured, survived the occupation; memories of forced evacuation, volunteering, adaptation to life without electricity; even just thinking or some creativity about war. It is also recommended to add photos and videos to the text.

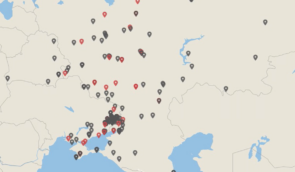

One of the photo testimonies on Svidok platform

One of the photo testimonies on Svidok platformAlmost 2,500 Ukrainians have already joined the platform. Here are some memories of Ukrainians:

“… A lot of military equipment entered Krasne, Chernihiv region, even the ground was shaking. The shots became increasingly powerful, and we got increasingly frightened. Then we lived in a cellar (thank God we have it!). The “orcs’” [Russians’] aircraft was constantly flying over our houses, it seemed it was touching our roofs. Then it started to drop bombs on us. This is how our fellow villager Roman was killed, and his father and brother got contusions. Then we were pummeled with artillery, aerial bombs… A woman and two children drove over a landmine while trying to leave Krasne. And we found ourselves in some kind of nightmare, we couldn’t get to Chernihiv… And we couldn’t get to Kyiv anymore… We saw how houses were burning in the village, animals were running around with glassy eyes, it was very scary,” a resident of Chernihiv region shared on the platform.

“In March 2022, I stood on the street in a line of several thousand people to a store, where only one person can enter at a time because they were afraid of theft. I was standing from morning to evening, repeatedly running to the subway to hide from tube artillery, Grad and Uragan MLRS shelling. Back then, air raid sirens did not go off to warn about such types of strikes, you just heard explosions and ran to the subway. I saw fires turning day into night with black smoke. Crowds of people were also shot at, it was near grocery stores that I saw the first corpses in my life. One such day, while I was under fire in search of food, a shell flew into my apartment on the second floor. It was pierced through with shrapnel along with an armored door. If I had been there, I would have been dead by now,” recalls an eyewitness from Kharkiv.

These testimonies, along with hundreds of others, have already been submitted to the International Criminal Court and the Prosecutor General’s Office, says Olena Kuk.

“We directly contact representatives of the International Criminal Court regarding the submission of Ukrainians’ testimonies about the crimes of the Russian Federation during the war. Details of the testimony submission are confidential for security reasons. But it is worth saying that the Court shows great interest in such personal stories,” she noted.

The project communications director emphasizes: the platform has several levels of protection, which allows contributors to remain anonymous. The developers closed the personal data of users for security reasons. Only investigators can contact them through a special account and only with the person’s permission. In addition, they also created a mechanism for documenting memories of Ukrainians who now stay in the temporarily occupied territory.

One of the photo testimonies on Svidok platform

One of the photo testimonies on Svidok platform“If a person is in the occupied territory, they can put a special note when creating the text. Then the post will be published only if they are no longer in danger,” technical manager Yuliya Tokarchukova explained.

Also, the platform is reliably protected from cyber attacks. And servers that store the memories are physically located in Germany and the US, so the Russians cannot directly attack them and erase the posts.

Moreover, foreign journalists, including representatives of The Times, The Economist, and Le Monde, keep registering on the platform. They can also contact Ukrainians through a special secure account and use the testimony in their materials.

Yelyzaveta Sokurenko, coordinator of the war crimes documentation department of Human Rights Centre ZMINA, which has been collecting information and documenting Russia’s war crimes against Ukraine since 2014, adds that in cooperation with Svidok, they seek not only to reproduce the truth about the crimes committed by Russia against Ukraine but also, thanks to the collected testimonies, to contribute to the restoration of justice for the victims and the punishment of the guilty: “It is important to join efforts in this process as it, unfortunately, is likely to be long. We are grateful to all people who suffered or witnessed war crimes but find the strength to speak about it.”

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.